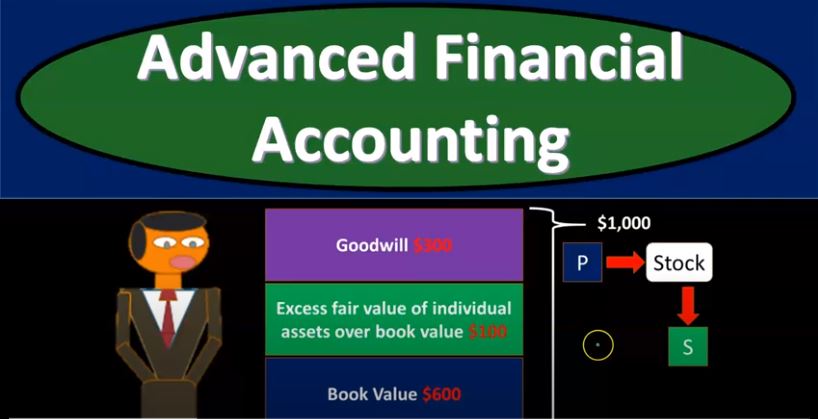

Advanced financial accounting. In this presentation we’re going to talk about the consolidation process with a differential we’re going to look at the component parts with a simple example a simple calculation, you’re ready to account with advanced financial accounting, consolidation with differential example. So here’s going to be the basic scenario for many of the practice problems we will be looking with. We have P and S, there’s going to be a parent subsidiary relationship in which we will be making consolidated financial statements. How did this situation take place what constituted this situation, we’re going to say that in this example, P is purchasing the stocks of S. So notice they’re purchasing the stocks of s and therefore negotiating the stock price, which we’re going to say is $1,000 here. Now to simplify this example, you first want to think about this as p purchasing 100% of the stock of s for $1,000. And then once they have control, anything over 51% would then be controlled.

We’re going to use the Example of 100%, then you’d have a parent subsidiary relationship at that point in time, at which point, you would think that consolidated financial statements represented P and S financial statements as if one entity would be appropriate or useful. So when we think about the consolidation process, then we got to think about Okay, what is PS books? And what are SS books going to be looking like? And then how are we going to basically consolidate them together, P will be recording their investment, this $1,000 on an equity method. So when they first purchase, if it was just for cash, you would think they would increase you know, an investment in s. And then they would record a credit to cash if they were to pay cash for it.

01:41

So notice they put the initial purchase on the books at the fair value, which we’re assuming is a $1,000. Given if these two individuals are these two companies are not related. There’s a market transaction. So the assumption like any market transaction, is that this 1000 is going to be basically the market price. That was got to was gotten to, through the negotiation. That’s what they’re going to be initially recording at the investment on the books for P. Now s down here note, nothing really happened to us in terms of the books, right? Because the stock was purchased up top. So SS books are basically the same as although all the stocks have been purchased and new ownership is there for us their general ledger accounts are in essence the same everything still on the books of s AP the book value. So then the question is, well, how do I relate the the purchase price here to what was purchased for s Now note that you would first think okay, well, if p purchased 100% of the stock of s, then you would think that they must have purchased it for basically the fair value of the net assets. That’s probably the first thing that you know what you would think right? I mean, if they if they negotiated 1000 How did he come to that 1000? Well, they must have said, Let me look at your balance sheet. Let me look at the assets and liabilities. Let me revalue that possibly, to what I think it is. And then and then your first thought would say, well, that would be it. Well, let’s build this up in our example, we’ll say, first we’ll think about the book value. So first thing you would think would happen in a negotiation, p would be looking at SS balance sheet, saying you’ve got assets and you’ve got liabilities. The net between the two at this point in time is the equity section. If the assets and the liabilities were valued at fair value, you would think then the book value would be you know, similar would be what the company would be worth if those were all the things that were involved in the negotiation. Right. So but it’s not necessarily the case that the book value here, as we can see doesn’t match the purchase price in this case, and it’s possible that the book value doesn’t match the fair value, because there’s some things on the books that aren’t recorded at fair value such as property, plant and equipment. And there’s a reason for it. It’s not like I’m not saying it should be recorded or and I’m not arguing that it should but it it’s on the books at depreciate should be depreciated cost.

04:01

So it’s quite likely that the fair value might be higher than that. So then you would think Alright, well then that 1000 must be from P then taking SS balance sheet and reevaluating the assets, increasing the value of the assets to things such as, for example, possibly property, plant and equipment and other assets. So that so that it would it would tie out to the price that they actually paid. In our example, we’re going to say the excess fair value of the individual assets over book value was only 100, though, so that would be 600 700. And the amount that was paid was 1000. So at this point, you might say, well, how can that be? How can it be that you know if I took the book value of the balance sheet assets minus liabilities, and then I fair valued it? How can it possibly be that P would pay more than that? I mean, wouldn’t it be the case that if they fair valued the assets and the liabilities and still paid more, that they must have done a run they did something wrong with the fair value Because that doesn’t make sense, right? Why would you pay more in a market transaction. And the reason you would pay more possibly is because the balance sheet doesn’t reflect something, something’s not on the balance sheet. It’s not that it’s valued wrong. It’s that it’s not on the balance sheet. And that thing would typically be the goodwill. So we’re going to say the goodwill here is going to be future earning potential that could be there above and beyond basically the fair value of the net assets. Why? Possibly because of something like a brand name, reputation. So this goodwill then is going to be the thing that we’re going to calculate. With this markets transaction, we need the market transaction typically to come to that goodwill. So we have p then purchasing the stock of s creating a parent subsidiary relationship.

05:46

In our example, the starting examples being p owning 100% of s, this will be the purchase price, we’re going to need to allocate that purchase price to the categories of what was purchased typically been the books value of S, which s didn’t change it’s on, it’s still got books, you know, they’re on using their book value, plus where we got the revaluation of certain assets and liabilities based on whatever that revaluation is going to be. And then the difference is going to be to Goodwill. Now, the calculation will typically look something and that’ll be the 1000, something more like this, like, we’re going to say, all right, that exchange took place p purchased As for $1,000, the book value of s at the point of purchase, we’re going to say is 600. So we’re gonna say, all right, the book value 600, then I’m trying to get up to this 1000. And then we’re going to say, all right, well, what’s the you know, differential between the book value and fair value, allocate into certain areas such as property, plant and equipment, the excess so we’re going to add to it then the fair value of the individual assets over the book value, which we said was $100. So we’re going to add to it the $100. That’s going to give us our subtotal, which we’ll say is the fair value. You have 700. So now we’re going to say, Well, if we revalued SS books, assets minus liabilities from the book value 600 to the fair value, it would then be 700. Then we would typically compare that to the purchase price and say, well, we paid 1000 for it. So what else is the difference here? Well, that’s going to be the goodwill. So we’re bottom line calculation will typically be goodwill here. So you can think about this, I would kind of think about this as the goodwill calculation, right? Kind of like you think about the cost of goods sold calculation. This is going to be kind of like your standard goodwill calculation. Now it’s possible for a book problem to just like a cost of goods sold calculation give you any of these unknowns, and make you figure out whatever the unknown that they don’t give you. Typically in practice, you would think about it in this fashion, right and be calculating in this way, get into goodwill. But if, for example, they don’t give you like this number, I wouldn’t rememorize another formula, just like I wouldn’t remember is the cost of goods sold formula. I would just, you know, memorize that. The formula and then plug in, of course, the unknown here, do your algebra and recalculated, just like you normally would. So you can see that I can the 1000, just like in our prior slide is the six for the book value, the 100 for the fair value difference, and then the goodwill down here, we’re just representing it. And now our typical kind of formula calculation, which is what you’ll typically be using in practice and deriving in this type of format.