Advanced financial accounting. In this presentation we will discuss inventory transfers and transfer pricing. Our objective will be to get an idea of what inventory transfers are what will be the effect of inventory transfers and how to account for inventory transfers when considering a consolidation process, get ready to account with advanced financial accounting, inventory transfers and transfer pricing. So in essence, we’re talking about the inventory going from one organization to another, we can think about this in terms of parent subsidiary type of relationships.

In essence, when we think about the consolidation process, we have inventory that would be going to one entity and then the other entity, what’s going to happen with the recording of those and how do we account for those basically transfers that have happened, you can think of the transfers as kind of like sales that would have happened. So that you will have to when you combine the financial statements, how are we going to deal with those activities, how are we going to eliminate basically any kind of transfer or intercompany transfer activity that is happening? So the physical movement of inventory inventory from one location to another, that’s going to be the inventory transfers. movement from parent to subsidiary, or subsidiary to parent is similar to moving inventory from division to division. So notice if you have a large organization, obviously, if we have inventory going from one area to the next, then oftentimes for internal accounting purposes, we want to think about the transfer the pricing, it’s going from one area to the next. similar kind of thing is what we want to apply. When we think about a parent subsidiary type of relationship. If it’s going to one company and then another company, then there’s a controlling interest between one and the other. And we’re going to do a consolidated financial statement. In essence, that is the same thing as a transfer from division to division is with regards to how we’re going to view it for the consolidation process. So in other words, it’s not a real sale is what’s happening we have a basically a transfer that is happening. So logistically, you can think about this as basically kind of intercompany Any sales when you’re thinking about what’s going to be the effect on the accounts? And how can you basically reverse the elimination entries, but it’s really a transfer that’s basically happening. And when you think about a transfer the logistics of the transfer, you’re really questioning, you know, the internal accounting, how are we going to account for the transfer of these items, these inventory units from one to the next, from a consolidation process? Of course, we’re thinking, what’s going to be the effect on the financial statements? And then how are we going to be able to remove in essence, the intercompany transaction that took place, the idea being that we’re, we’re acting like one entity, so we can’t really have a sale to ourselves.

02:39

So how can we basically eliminate the effects of a sale that looks it’s basically happening to ourselves with it with regards to an intercompany transfer, so income tax affects income tax effect transfer pricing decisions, income taxes, affect transfer pricing decisions, so we want to take into consideration the tax effects when we have these intercompany type of transfers from inventory. From say one entity to another, that will then be consolidated income taxes on selling companies, unrealized gross profit will be eliminated. In other words, if you have a sale from one company to another, which was a subsidiary company, and the other company had not yet sold that inventory, then that’s going to be unrealized, unrealized gross profit, it’s a phantom sale, the sale didn’t really happen if it’s an intercompany type of transaction. Therefore, the tax related to it should be eliminated. elimination of all or some. So now that we think about the elimination process, if we think about this intercompany type of transaction transaction that we now need to eliminate, there can be a problem or there’s going to be questions that will arise if it’s less than 100% owned subsidiary. In other words, if we have an intercompany transaction where we’re basically saying, hey, look, we sold something to ourselves and in essence, there’s a transfer that basically is acting like a sale and one company is the parent company of another company and the sale Basically intercompany if it’s a 100% owned subsidiary, then the question it’s easy to then say, well, we just basically need to eliminate the effects of that intercompany transaction, we can’t have transactions to ourselves, in essence. However, if it’s less than 100% owned subsidiary, then we’re stuck with this question as to well, if it’s less than 100% owned, we’re still going to do a controlling a consolidation process. But what do we do with the non controlling interest with regards to the to the reversal process of the intercompany sale? Well, we’re going to break this down. And this will make a lot more sense if you take a look at the practice problems, but this is how we’ll break them down in category we’re going to break down between a downstream sale. So we have a we have a non controlling interest involved here, a parent subsidiary relationship, the subsidiary is not 100% owned by the parent. So now we need to think about how we’re going to break out the reversal process of these intercompany transactions. If the sale is going from the parent to the subsidiary. That means the end Inventory was sold from the parent to the subsidiary, we’re going to call that a downstream sale. And that means that all of the gains from that went to the parent. So since all the gains went to a parent, we don’t need to think about breaking this one up between the parent subsidiary with regards to the non controlling interest and the controlling interest percentages.

05:18

So because all the profit goes to the parent sharing, sharing is not needed or not done in the reversal process. However, if you’re talking about an upstream transaction, that being the case where it’s from STP, the subsidiary making the sale upward, when the subsidiary then makes the sale and records basically like the income on the sale. Now, now, you know some of that you would would go to the controlling interest to the parent company, some of that net income that would be affected. And some of that net income in theory would be going to the non controlling interest portion that’s less than 100% own the stockholders that aren’t the parent company. So that’s when you have to think about this basically non controlling interest. So The upstream transactions, the sales going from S to P, when you got to think about this kind of breakout, so because s profits are allocated to both controlling and non controlling interest as being the subsidiary shareholders, you need to allocate part of the deferral to the NCI or the non controlling interest. So we’ll see many examples of this as we go through the practice problems, inventory transfer relation for consolidated financial statements. So basically, when do you When do you realize that the inventory related to this transfer, so it’s realized when the parent or subsidiary purchaser has resold the inventory in an arm’s length transaction? So in other words, you know, when do you actually recognize the the sale that took place? Well, if there’s an intercompany sale of inventory, so it went from P to s, you sold inventory was basically transferred from P to s. When do you When do you get to recognize the unrealized gain? Well, when the resale happens When an actual sale took place to someone outside what we’re thinking of as the total entity, so when s re sells that inventory to someone outside, which means an arm’s length transaction, someone who’s not related to the organization, that’s when when you can realize basically game that took place.

07:18

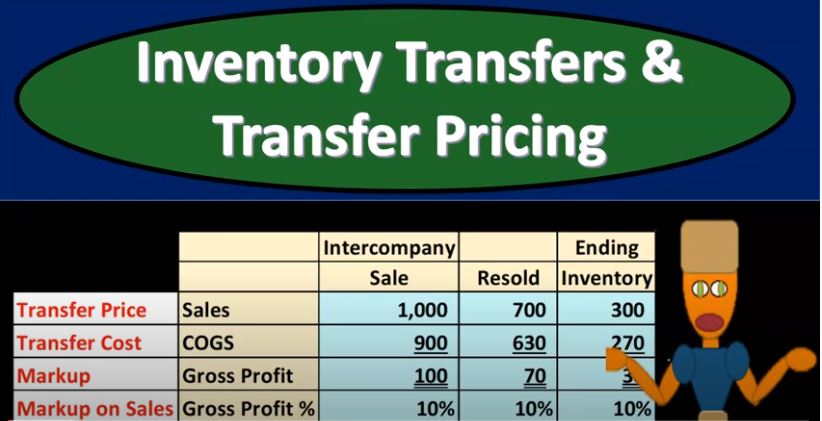

So in other words, if there was a sale from P to s, then you could result in unrealized gain, which would then be realized when at the point in time that s then resells the inventory, because that’s going to be the point in time that the inventory was actually sold on basically a market at an arm’s length transaction. So let’s take a look at what this might look like just in general. And then we’ll think about some terminology that we could have. So let’s say we have a situation where there’s an there’s an intercompany sale between a parent subsidiary type of relationship. So the general thing that we need to think about is okay, well, let’s think about the normal sale in terms of the normal terms. We would use, we would say, Alright, well, there’s a sale that took place, and the cost of goods sold was 900. The gross profit, then in this case would be 100, gross profit percent, but 100 divided by the 1000 would be 10%. So that would be the normal kind of lingo we would have if it was an arm’s length transaction. If it’s an intercompany transfer, then you might just rephrase this and different lingo. So just realize it just it’s the same thing. So just realize, you know where you’re working with, but you might hear this the same items with a different lingo when it’s going to be intercompany, a different format of saying this, right? And that might say, what’s the transfer price, meaning the transfer price is going to indicate Well, it’s not like a sale. It’s an internal kind of sale or internal transfer that would indicate to you that it’s going from division to division, or to like parent subsidiary, and then we’re going to call this transfer costs, which would then again, indicate that it’s something internal as opposed to an arm’s length training. Actually outside, that’s going to give us the markup. So here’s the markup. So when it was transferred from this division to the next division, we’re not going to call it you can call it non instead of gross profit, you can call it, you know, markup, that’s the markup that took place during that transfer, and then the markup on the sales will be the percentage. So that’s some different terminology that you can you can think through as you work through these, you know, problems, then you want to think about how much of it was resold. So if it went from P to s, the question is, is it still hanging out on SS on the subsidiaries balance sheet as income? I mean, as inventory or did they resell it? Or if it went from S to P over here? Is the parent still holding on to it or did they sell it? So we got to think about the amount that was resold. And then we could say okay, this is the amount of sale this is the amount that was resold. This is the amount that is still left than Indian inventory. So in other word, If it was sold from P to s parent to subsidiary, they sold it to the subsidiary, the subsidiary then has it been the subsidiary of that $1,000 sales price amount measuring this in, you know, $1,000 they sold results 700 of them to get to the Indian inventory, Indian inventory is still being reflected on SS books of the 300. So the 700 amount that has been sold then you would think now, it’s proper to realize some income at that point in time because it was sold to someone outside at arm’s length transaction. The 300 over here representing inventory that’s now on SS books represents a portion of unrealized gross profit that happened on you know, PS books for the original for the original sale, so we’re gonna have to basically think about how to how to deal with that.

10:54

So this is going to be kind of the launching pad or the starting point or start of what we need. In order to build the reversing process, so then we’ve got the cost of goods sold. Same thing, here’s the cost of goods sold for the original sale, they resold it. So of that 900. The 630 is the amount that was resold and then we got the 270, then gross profit 70% resold, or 70 resolved 30. Still in Indian inventory, obviously, you could subtract this down this way as well. You can also think of this as well. If you know this, you know, if you know this amount, and you know that 10% is the gross profit, then you know that this is 90%, right? The 1000 times 90% would be this one minus 10%. So then if you know the amount that is resold, you can say okay, well 90% of that, if we haven’t even margin would be the 630. And the 70. here would be 10%. Of course, that’s the 7000 or in many cases you might think of Well, I know these numbers for sure. Because I know the sales that happen from P to s are intercompany sales in a certain period. And maybe you know this number, so you might then know the 300 Indian inventory because it’s still possibly in the Indian inventory. So that’s so then you can of course back into the amount that was resold back into the amount that’s resold, then you can, you know, figure out, this is going to be 90% of this number. And then this is going to be 10%, or this minus this. And you can figure this number multiple ways this minus this, or 90%, of this number, and so on. So, in practice, you will probably in practice, you would generally know these numbers, and you might probably know this number for sure. And then you can kind of back into the other numbers and a book problem. They can basically give you any set of numbers with it with an unknown here and you want to be able to think about it in a table type of format and then figure out whatever you know, whatever unknown, they get to you, and if they do They may give it to you in this format. In terms of terminology, in our book problems, I’ll usually still be using, you know the normal terminology for sales just because it’s it’s easier to think through. But then if you hear this terminology, just note that of course that all that does is indicate, in essence that it’s an intercompany transaction, which can be a useful tool.

13:23

So fully adjusted equity method. So what is the fully adjusted equity method that’s in essence, what we’re going to be using? For most of the problems, it’s what would make the most sense. And when you can think about it in general as basically the equity method, meaning parent companies reflecting their investment in the subsidiary, using the equity method, reflecting their portion of the net income on the books and their portion of basically the net assets on the books. But then what about these adjustments that are happening with the consolidation? So now we’ve got these adjustments that are happening related to inventory and whatnot. Well, they’re now on SSI. His books, but we’re still going to reflect them in the fully adjusted equity method, because that’ll that’ll they will be, you know, taken into account within the elimination process. So we will be taken into account with the fully adjusted equity method some of these adjustments we’re going to have to be dealing with with the intercompany transfers of inventory. So unrealized profit on intercompany inventory transfers are deferred on the parents books. This results in net income equaling the controlling interest in the consolidated income and retained earnings, equally consolidated retained earnings. So let’s read that one more time unrealized profit on intercompany. Inventory transfers are deferred. So we’re going to recognize those deferrals within our equity method process on the parents books. What’s the result? The net income equal equaling the controlling interest on the consolidated income? So on the consolidated income, it’s kind of like the key point here meaning Erica company isn’t recording these transactions. So we’re not really tying into what we would normally time which is what’s recorded by s, because we’re taking into consideration that consolidation transactions, but it will tie in once we enter the consolidation entries and retained earnings equaling consolidated retained earnings, same idea with regards to basically the balance sheet side or the you know, equity retained earnings side of things, journal entry on parents books to defer unrealized gross profit. So, what are we going to record in terms of an actual journal entry, we’re going to debit the income from s that remember the income from so the subsidiary represents our portion of the net income of s and we’re going to reduce it that’s normally a credits normally like net income with a credit we’re going to reduce it with a debit and we’re going to credit the investment in s the investment in s reflecting the balance sheet information or an asset, which again will be going down due to the deferred unrealized, gross profit And then we’ve got this breakout once again with the downstream transactions and the upstream transactions. So if it’s a downstream transaction, that means it’s going from the parent to the subsidiary, the entire amount is deferred.

16:12

So downstream transaction, the entire amount is deferred. But if it’s an upstream transaction, then the parents proportionate share of unrealized gross profit is deferred. So in other words, if it’s a downstream transaction, and we’ll actually put together a worksheet in our practice problem going from parent to subsidiary, we only have to consider we could take the whole amount basically, and allocate it to basically the parent, which would be the investment in s and the income from s the whole amount here where if it was an upstream transaction from the subsidiary to the parent, then we got to take the amount and multiply it basically times the controlling interest portion to consider this entry as we think about the equity method, after inventory on hand is sold to an outside party. The deferred amount is recorded in the period of the sale by reversing the deferral on the parents books. So note that this is going to be a deferral process, what’s going to happen then is that there’s going to be a sale that takes place once the sale takes place, then there’s going to be a reversal process. So you can think of a general idea, then we’re always going to have to be considering basically two years, our general principle will be, well, if we’re if we’re doing a consolidation this year, that means at the beginning of the year or at the end of last year, there’s income, there’s there’s going to be inventory on the books maybe related to an intercompany transfers, and we’re gonna have to reverse the deferral of that, because the assumption is that that inventory that was on the books as of the end of last year was sold this year, and if that’s the case, then we got to reverse the deferral for the prior year. And then in the current year, that we’re going to have those sales that took place the intercompany sales and reflected possibly in Indian inventory. And those are going to be the deferral transactions will have to make in the current year. So we’ll be considering then usually two years of data, we’re gonna have to say notice how we’re gonna have to break this out. And we’ll do this in a systematic way as much as possible, we’re going to have to say, all right, there were downstream transactions and upstream transactions in the prior year, that we’re going to have to basically reverse in the current year, and then there’s downstream transactions and upstream transactions into the current year, that that we’re going to have to account for so we’re gonna have to break those out. Because the downstream transactions we had we could take the entire amount and the upstream transactions we have to break out and last year’s ones are going to be the reversals. And then this year’s ones are going to be the ones that we record like this up top, consolidation entries, income statement, adjustment to sale and cost of goods sold. So when we do the consolidation entries, we’re going to have to do an adjustment to the sales in the cost of goods sold for the for the transactions that took place in the current year, which if you think about them as one entity, shouldn’t have take place. So the cost of goods sold in the sales in other words being overstated, then the balance sheet adjustment to inventory. So the inventory account is obviously going to need to be adjusted as well on the balance sheet side of things. The result is the show financial statements as if the intercompany transfer transfer had not happened. So of course, that’s going to be the end result when we combined the parent and the subsidiary together, we got to think about how can we basically reverse the thing out to these intercompany transfers had not taken place? What would this look like if we had just one entity that didn’t have these sales basically, in essence to themselves, as it would be the case or acid how we would think about it, if they were one entity