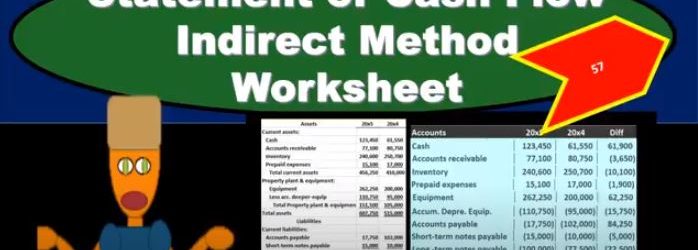

In this presentation, we will put together a worksheet that will then be used to create the statement of cash flows using the indirect method. To do this, we’re going to use our resources which will include a comparative balance sheet, and income statement and added information. Remember that in practice, we’re typically going to have a comparative balance sheet RS here being for the current year 2005 and 2000. x for the prior year. So we need a comparative to time periods in order to create our worksheet. This will be the primary components that we’ll use to create our worksheet. We will need the income statement when I’m creating the statement of cash flows mainly to check up on some of the differences that we will have in our worksheet. And then in a book problem will typically be told some other things related to for example, purchases of or sales of equipment, borrowings, if we had any cash dividends or any dividends at all, this is added information we would Need. In practice, of course, we would just be checking on these things by looking at the difference and going back to the GL. And just taking a look at those differences in order to determine if we have any added information that needs to be adjusted on our statement of cash flows.

Posts with the Cash tag

Statement of Cash Flows Direct Method Vs Indirect Method

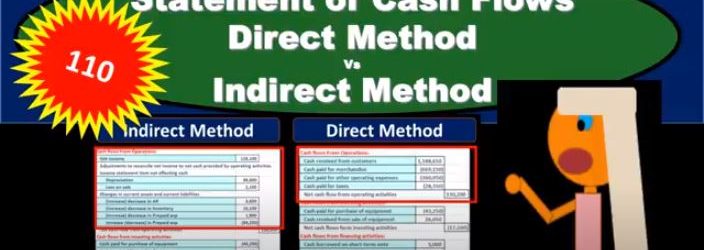

In this presentation, we will compare and contrast the direct method versus the indirect method for the statement of cash flows. It’s important to note that when we’re comparing the direct and indirect methods, we’re really only talking about the top part, the operating activities portion of the statement of cash flows. In other words, the investing activities and financing activities and in result will remain the same, we’re going to end up with the same result, which of course, will be the Indian cash that we can tie out to the balance sheet. And we’ll have the change of cash here, which is really kind of the what we’re looking for in the statement of cash flows. What’s going to differ is the operating activities, why are they going to differ? Why would we have the operating activities differ? Remember that the operating activities have to do with kind of the income statement you can think of it basically as the income statement being reformatted to a cash flow statement versus an accrual statement. So the income statement that we use is on an accrual basis, and we recognize that Revenue when it’s earned rather than when cash is received expenses when expenses are incurred rather than when cash is paid, that’s gonna be on an accrual basis.

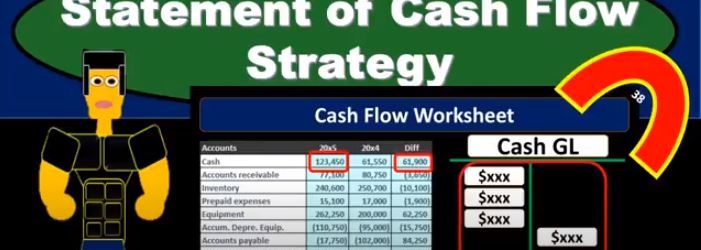

Statement of Cash Flow Strategy

In this presentation, we will take a look at strategies for thinking about the statement of cash flows and how we will approach the statement of cash flows. When considering the statement of cash flows, we typically look at a worksheet or put together a worksheet such as this for my comparative balance sheet, that given the balance sheet accounts for the current year and the prior year or the current period, and the prior period, and then giving us the difference between those accounts. So we have the cash, we’ve got the accounts receivable inventory, we’re representing this in debits and credits. So this is in essence going to be a post closing trial balance one with just the balance sheet accounts, the debits represented with positive and the credits represented with negative numbers in this worksheet, so the debits minus the credits equals zero for the current year, the prior year. And then if we take the difference between all the accounts, and we were to add them up, then that’s going to equal zero as well. This will be the worksheet that we’re thinking about. Now. When can In the statement of cash flows, we can think about the statement of cash flows in a few different ways. We know that this, of course, is the change in cash, this is the time period in the current time period, the prior year, in this case, the prior period, the difference between those two is the difference in cash.

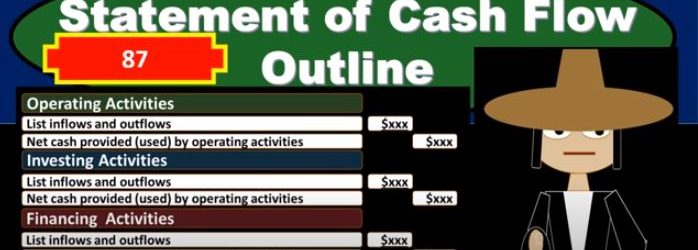

Statement of Cash Flow Outline

In this presentation, we will take a look at a basic outline for a statement of cash flows. In order to do this, we first want to give an idea of how the statement of cash flows will be generated. So we can think about these components of the statement of cash flows and where they come from. Typically, we will have a worksheet such as this that we will use in order to generate the statement of cash flows. That statement of cash flows, having three major components, operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Our goal here is going to be to fill out these three components and typically we will use a worksheet such as this on the left. The worksheet is just basically a comparative balance sheet that we have here that we’ve reformatted from a balance sheet to just a trial balance type format, a debit and credit type format. So you can see that we have our balance sheet accounts, and we are imbalanced by having the debits the positive and the credits be negative or debits. Minus the credits equaling zero, given it’s an indication that this period, the current period that we are working on, is in balance, the prior period, same thing. So we have two points in time for to balance sheet points the prior year, or period the prior year in this case and the current year. And then we just took the difference between these two columns. And if we have something that’s in balance, here, the debits minus the credits equals zero, something that’s in balance here, the debits minus the credits equals zero. And then we take the difference of each line item in these columns. And some of those differences, it too must add up to zero. So in essence, what we’re going to do in order to create the statement of cash flows is find a home for all these differences. And that’ll give us a cash flow, a concept of the cash flow statement. We’ll get into more detail on how to do that when we create the cash flow statement. But as we look at the outline, keep that in mind. So here’s going to be the basic outline for the state. cash flows, we’re going to have the operating activities. That’s going to include a list of inflows and outflows from the operating activities. And then we’re going to have the net cash provided by the operating activities. Now, this list of inflows and outflows for the operating activity will be the most extensive list because the operating activities are in relation to you can think of it as similar to the income statement.

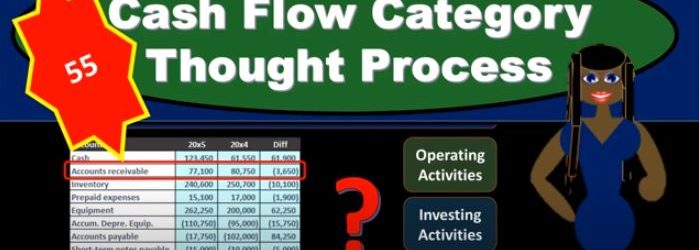

Cash Flow Category Thought Process

In this presentation, we will think about the thought process to know which category a cash flow should be entered into whether it should be operating, investing or financing activity. When putting together the statement of cash flows, we’re usually going to have a worksheet, which will typically have a comparison of balance sheet accounts. And we also might just have test questions that will ask us, where should this cash flow go? And that’s going to be a common kind of question that we’re going to have whether we build the entire cash flow statement from scratch, or whether we’re just asking test test questions and trying to know what types of Cash Flows we’re talking about. It’s also important for practice as well so that we can understand when we’re thinking about cash flows, where do they belong? What are these cash flows mean? What are they doing for us? What are they doing for the company? Are they part of the operations? Are they part of investing? Are they part of financing? If we look at a worksheet like this to build the statement of cash flow, typically we’re going to look at a balance sheet for two periods. So here our balance sheet for these two periods. And we’ll have the difference between the two periods in terms of the balance for these balance sheet accounts. So we’ve got cash, accounts receivable, inventory, prepaid expenses.

01:13

Now what we’re going to do is we’re going to take the change in cash, that’s going to be the end result on our statement of cash flows. And we’re going to kind of back in to that end result by looking at the change in the other balance sheet accounts and tried to figure out what’s causing this change. So we’re going to go through all the other balance sheet accounts, look through these changes. And we know that if we look if we add them all up, they add up to zero. Why? Because the debits and credits for one year, add up to zero the debits and credits for the other year add up to zero. In other words, the debits minus the credits equals zero. And therefore the difference between the two years debits and credits the change will add up to zero. So we know that’s the case and we know that if we add up then everything except cash Then the result will be the difference in cash. So that’s how we’re going to kind of work and put together our statement of cash flows. So what we need to do then is we’re going to take a look at these changes in receivables, changes in inventory changes in prepaid expenses, and then try to determine where does that change belong? Before we get into any other question is, is the change of inventory and operating, investing or financing activity? And is the change in long term notes payable? Is that going to be an operating investing or financing activity? Our goal here is to go through a thought process to see if we can think through more clearly which category these these should be belong to. So what’s the most common journal entry in this account? It’s going to be our first question.

02:48

Whatever account they’re given us here, we’re going to say it let’s think about the most common journal entry that’s related to this account, there’s typically going to be one or two journal entries that are going to be very common and we want just right down first, once we know the most common journal entry, then we’re going to ask is an income statement account involved? So when we think about whatever account we’re dealing with, we’d write down the journal entry and say, Okay, is there an income statement account involved? Is there a revenue account or an expense account involved? If the answer is yes, then it’s probably the change that we’re dealing with is probably something that should be in the operating activities. Because remember, the operating activities is kind of like the income statement on a cash basis. So if we’re dealing with something that’s this change has something to do with the income statement, then it’s going to be something on the operating activities. Typically, if the journal entry has nothing to do with the income statement, there’s no revenue or expense accounts involved in the normal journal entries related to these accounts, then we’re going to ask the question, are we purchasing or selling an asset? Because it’s so if it’s not operating, this means that it’s not operating therefore, We’re trying to see if it’s going to be investing activity. And that typically means we’re purchasing or selling an asset. If it has to do with, for example, property, plant and equipment, or some other type of investment, then it’s going to be an investing activity. And then if it’s not, then it’s going to be financing. And of course, financing is going to be dealing with notes, something that we’re dealing with that doesn’t deal with operating activities in terms of the income statement, no revenue and expenses, and typically doesn’t have assets involved either, because what we’re doing is funding the company. So that’s typically going to be something that deals with cash and subtype of liability or the equity section. So this is going to be our thought process if we go through each of those line items, and think about each account on the balance sheet.

04:46

And then try to go through this thought process and think okay, which category are we going to be putting this change to? Now, this looks a little less intuitive than we might think at first glance here because no one We’re doing we’re looking at the balance sheet accounts. And we’re trying to see what category these things are going to fit into. And remember that the operating activities I’m keep on comparing that to the income statement. And you might be thinking, well, these are all balance sheet accounts. Why do you keep mentioning the income statement. And note, what we’re doing here is we’re really kind of backing into the activity is happening by looking at the change in two points in time. So we’re kind of still looking at the income statement activity type of accounts, we’re looking at change, we’re looking at activity, even though we’re doing that by looking at the change in two points in time to balance sheet accounts, which are points in time. So when we look at the change in accounts receivable for example, if we go through our thought process, we’re going to say okay, accounts receivable was at 80,007 50. In the prior year, end of the current year, it’s at 77,100.

05:51

That means it went down by 3650. So our goal here is just to determine which category That change belongs to it’s an operating, investing or financing. And if we think about that, then we could think Well, what’s the normal journal entry related to accounts receivable? We’re going to have a debit to accounts receivable and a credit to sales. That’s going to be our normal journal entry that we’ll have related to accounts receivable. And we can see there that sales is an income statement account. So we know that it is an income statement account involved, we’re going to say yes, therefore, it’s an operating activity. So note what we’re doing here, we’re looking at the change in a balance sheet account. We’re looking at the change in the balance sheet account, then ask yourself, what’s the normal journal entry related to this account? And if we think about the normal journal entry related to accounts receivable, that’s a sale of something on account. So accounts receivable goes up when we make a sale on account, and we credit revenue and revenue is clearly an income statement account. So this Change, then that’s what we’re going to think through, we’re going to say that change looks like it belongs somewhere in the operating activities. Because we’re dealing, we’re really kind of backing into sales. That’s what we’re really looking at. And we’re going to do that by writing down the journal entry. Let’s look at another account. We’re going to pick equipment now. So we’re just going to go through all these changes. And we just got to find a home for all these changes.

07:21

When we when we make the statement of cash flows. We got to find a home for them in either operating, investing or financing. And we’ll end up with the change in cash, which is kind of like the bottom line. The bottom line will be cashed at the end of the day. So we’re going to find a home for the equipment. Where’s that going to go that change? Well, if we think about the journal entry for equipment, then if we buy equipment, we’re going to debit equipment, and credit cash and possibly credit like a note payable, some type of financing. But if we pay cash for it, this would be the most simplified journal entry. Even if we had a note there’d be no Part of it that would be on the income statement, one asset went up, the other asset is going down. So therefore, is the is an income statement account involved? No. So we’re purchasing or weren’t, so it’s not going to be an operating activity. And then the next question is, are we purchasing or selling an asset? In this case, yeah, we’re purchasing an asset. And that means that it’s going to be an investing activity. So and this was the confusing thing for me when I first started learning this thing, because investing activities, I had a different conception of what investing is to invest in something like any asset any anything we purchase in the business that we’re not consuming now is an investment to the future. In terms of the cash flow statement, we’re trying to spend our cash in order to put our money somewhere that’s going to help us make money in the future. That’s going to be some type of investment. So in this case, it’s going to be an investing activity.

Classification of Cash Flows

In this presentation, we will take a look at classifications of cash flows on the statement of cash flows, there’s going to be three major categories on the statement of cash flows. Those will be operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. So our goal here, when we go through the statement of cash flow as we work through the statement of cash flows is going to be in part to decide which area these cash flows should go, should they go into operating, investing or financing. It’s going to be common questions and common problems and really just information we need to know when reading the statement of cash flows. So we’ll start off with the operating activities. We’re just going to look at the major components of the cash flows within the operating activities. So we’ll talk about inflows and outflows. Remember what we’re talking about here is cash. So when we’re talking about the statement of cash flows, we’re talking about cash flows, the cash that goes into the company, they cashed out goes out to the company. We’re going to talk about inflows and outflows here related to operating activities. Before we go into the list of inflows and outflows related to operating activities, we want to know first, that operating activities is going to be similar to us thinking about the income statement on a cash basis. So when we think about the operating activities were really thinking or one way to think about it would be that if we were to have the income statement on a cash basis, then what would the inflows and outflows be that’ll basically be what are in the operating activities when we get to the thought process in terms of how to determine operating investing and financing activities.

Statement of Cash Flows Introduction

In this presentation, we will introduce the financial statement of statement of cash flows. When thinking about the statement of cash flows, we want to compare and contrast the reasons for it to what the other financial statements are providing us what information in other words, are we going to get from the statement of cash flows that’s not on the other financial statements, those being the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of equity, we’re mainly comparing against the income statement, because the statement of cash flows going to give us some similar information. It’s going to give us information over time, what’s happening over time, unlike the balance sheet, which is going to have a point in time. So we’re still looking at at timing what is what is going on over time. That’s typically our income statement, which measures performance. The major goal of the income statement is to measure performance, how have we done how much work have we done, revenue minus expenses, revenue being recognized when we earn the work when we’ve done the job expenses when we We’ve incurred something in order to help generate in the same time period. And that’s going to be the net income. What that doesn’t do, however, is measure cash flow. And when we first learn about the income statement, that’s going to be a real big distinction we want to look at, we want to say, okay, the income statements on an accrual basis.

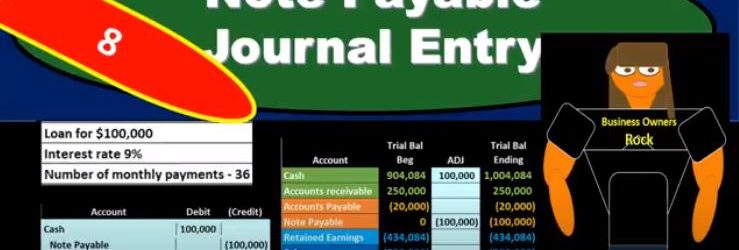

Note Payable Journal Entry

In this presentation, we will record the journal entry related to a note payable related to taking out a new loan from the bank. Here’s going to be our terms. We’re going to record that here in our general journal and then we’ll post that to our worksheet. The trial balances in order assets, liabilities, equity, income and expenses, we have the debits being non bracketed or positive and the credits being bracketed or negative debits minus the credits equaling zero net income currently at 700,000 income, not a loss, revenue minus expenses. The difficult thing in terms of a book problem, when we record the loan is typically that we have too much information and this is the difficult thing in practice as well. So once we have the terms of the loan, and we have the information, we’ve already taken the loan out, then it’s the question of well, how are we going to record this thing? How are we going to put it on the books and if we have this information here, if we have a loan for 100,000, the interest is 9%. And then the next number of payments that we’re going to have, we’re going to pay back our 36. Then how do we record this on the books? Well, first, we know that we can ask our question is cash affected? We’re going to say, Yeah, because we got a loan for 100,000. That’s why we got the loan.

01:14

So cash is a debit balance, it’s going to go up with a debit, so we’ll increase the cash. And then the other side of it is going to be something we owe back in the future. And that’s going to be note payable. And that’s as easy as it is to record the initial loan. The problem with this the thing it’s difficult in practice, and in the book question is that we’re often given, of course, the other information, like the interest in the number of payments, and possibly more information that can cloudy up the what we’re doing, and the reason these are needed, so that we calculate interest in the future, but they’re not really We don’t even need that information to record the initial loan. All we need to know is that we got cash and we owe it back in the future. And you might be asking, Well, what about the interest we owe interest in the future as well? We do, but we don’t know it yet. And that that’s the confusing thing interest, although we we will pay interest and we know exactly how much interest we’re going to pay in the future. We don’t owe it yet. Why don’t we owe it yet? Because we’re going to pay back more than 100,000. Why don’t we Why don’t we record something greater than 100,000? You might say, because we know we’re going to pay more than 100,000. And that’s because the interest is something that it’s like rent. So we’re paying rent on the use of this 100,000. And just like if we if we had a building that we rented, that we’re using for office space, we’re not even though we know we’re going to pay rent in the future. We’re not going to record the rent now. Because we haven’t incurred it until we use the building.

02:41

So the same things happening here. We know we’re going to pay interest in the future we’re no we know we’re going to pay more than 100,000 but it hasn’t happened yet. We haven’t used up we haven’t gotten the use of this hundred thousand and therefore haven’t incurred the expense of it yet. So the interest and is something we need to negotiate when making To turn off the loan, but once the loan has been made, and we’re just trying to record it, it’s not going to be in the initial recording. It will be there when we calculate the payments need and the amortization table. So the initial recording is pretty straightforward. We’re just going to say okay, cash is going to go up by 100,000. And then the notes payable is going to go up from zero in the credit direction to 100,000. So what we have here is the cash increasing the liability increasing, although we got cash, there’s no effect on net income because we haven’t incurred any expenses. We’re going to use that cash most likely to pay for expenses possibly or pay for other assets or pay off liabilities in order to help us to generate revenue in the future. But as of now, we’ve gotten we increase an asset and we increase the liability

Bond Retirement

In this presentation, we will discuss the journal entries related to the retirement of bonds. the retirement of bonds just means that we’re going to pay off the bonds in some form or another at some time or another, meaning the bonds are going to go away. Typically, that’ll happen at the maturity date at the end of the bond. So for example, if we have a bond on these terms, with the face amount of 240, the issue price of 198 for 80, for 15 year bonds, they’re going to be semi annual. What would happen is when we put this on the books, we would put it on the books as cash we got for the 198, the bond payable on the books for 240, and then a discount. And then of course, over the life of the bond, we would be paying interest for that 15 year time period two times that’s 30 payments. And then at the end of this we would also be be amortizing out the discount to get rid of it, to make it go away to the interest and then By the end of this time period, the discount would be zero. And we would only be left with a bond on the books. In other words, at the maturity date, we would have something like this on our trial balance, the discount is now zero. And the bond is on the books at 240, which is the face amount of the bond, if it were a premium, it would be it would be the same in that we would be left with just the bond amount and the premium would be gone to zero. And now it’s just like anything else that we don’t have to deal with interest at this point or anything else, we just need to close out the bond. And so it’s just like any other liability, we’re just going to pay at the maturity date. That’s how we’re going to retire it. So this is a 240 credit, we’re going to make it go down by doing the opposite thing to it a debit, and we’re going to pay cash, cash is a debit balance, we need to make it go down. So we’re going to credit cash. So this is going to be our journal entry. We’ll debit the bond make go away, and then we’ll pay off the cash. When we post this then the bond payable will be here. Here, it’s going to go it’s a credit, we’re going to debit it, making it go away to zero, and then the cash has a debit balance, we’re going to credit it making the cash go down. So it’s a pretty straightforward journal entry.

02:12

The only confusing thing about this journal entry is that it happens at the end of the bond term. So when we’re talking about book questions, we often don’t get asked it because usually we’re concentrating on how to calculate the interest how to calculate the face amount of the bond, how to record the bond, how to amortize the the bond, discount or premium. And we don’t really typically get all the way to the end of the bond, the retirement the maturity date, to record the end transaction oftentimes, and it’s a pretty easy transaction if we were to do so. And it’s a lot easier to if we can actually see the trial balance. When you see the trial balance, you say, oh, there’s a liability there. We’re going to pay it just like we would if it were note payable at this time. It needs to go down and then we’re going to pay it off with cash. Now it is possible for us To have a callable bond that we’re going to retire before the end of the bond date before the maturity date. So in other words, in this case, we have the bond on the books of 240,000. And we have the discount of 338 748. And therefore, if we were to calculate the carrying amount, we’d have 240,000 minus 238 748, or two a one 252. This 201 252 is the carrying amount of this bond payable. This is something that we owe in the future. If we can pay it off at this point in time for some cash that’s going to be less than this amount, then we’re going to have a gain resulting in a gain. And if we are paying it off early for something more than this, we’re going to have a loss. So let’s see what that’s going to look like.

03:52

The gain or loss can be confusing here. When we’re talking about a bond. It’s easier to get to that point by just doing the journaling So if we have all this information, especially if we have the trial balance, because then we can see what accounts are debited and credited on the trial balance or which accounts have a debit or credit balance, then it’s a lot easier for us to construct the journal entry. So the first is going to be given to us, we’re going to say that the cash that we’re paying is 230,000. That’s gonna have to just be given in the problem because that’s the callable price that’s how much we’re able to purchase these bonds for. So cash is going to go down because remember, we are buying them back basically, or we’re we’re paying them off early before the maturity date. So it’s going to be 230. Then we’re going to say that the bond payable has to go off the books. Now the bond payables on the books at 240,000, we can see it’s a liability, it has a credit balance. So to take it off the books, we do the opposite thing to it, a debit for whatever it needs to be to make it go to zero, the discount. Same thing we need to do whatever we need to do to make it go to zero because it’s Gotta go away. So when we construct the journal entry, we just know that we just got to do whatever we need to do to make it go to zero. If you have a trial balance in front of you, that’s easy to do, because we can see the discounts on the books at a debit. And we need to do the opposite to make it go down, which is a credit. If you’re looking at a book problem that doesn’t give you a trial balance, and just tells you that the bond is on the books at a discount, then you got to think through it. And one way to think through it might be to say, well, the bonds is a liability, it must be a credit, that discount means that we’re making the bond go down, because it must be decreasing, we’re having it less than the state, the face amount, the sticker price.

05:40

And since it’s a credit, the thing that makes a credit go down would be a debit. So that discount must be a debit because these two are really combined together. And a discount means that we we really the net of the two are below the face amount price, so this must be a debit. So if it were a premium, then this amount be increasing or greater than the face amount, and it would be a credit normal balance. Once we know that this is a, this is a debit normal balance for a discount, then we can do the opposite thing to it to credit it to make it go down. And then of course, we just need to figure out what the difference is we’ve got credits of 230,038 748 minus the 240. Debit means we need a 28 748 debit. And that of course, in this case, I’m going to say it’s a gain loss account here because it could have gone either way. But if it’s a debit here, then it’s on the income statement. That’s going to be a loss. And you just got to basically start to be able to recognize that why would that be a loss? Well, you can think through that. We paid 230 versus the carrying value, or you can also just think well, if it’s a debit on the income statement, It’s acting more like an expense, meaning expenses have debit balances, they go up in the debit direction, and they bring net income down.

07:08

Revenue has a credit balance, it brings net income up. This is acting like a, an expense because it’s a debit balance. If we debit the income statement, it’s going to make net income go down, that means it must be a loss rather than a gain, which we would think would make net income go up. So the other way we can think about this is to is remember, the carrying value is going to be the 240,000 minus the 38 748. So this is kind of a value that we owe on the bond. And it’s a liability, that’s kind of the value we owe and we paid more than the value that we owe. So that’s going to be a loss in this case. And that’s another way you can think through it being a loss. So if we post this out, then we’re going to say that the gain or loss 28 748 Here, making the income statement accounts go up, kind of like an expense bringing net income down. The bond payable will be posted here, it’s going to make the bond payable go to zero. That’s why we are retiring. It’s making it go away. And then we’ve got the discount, it’s going to make the discount go to zero because we’re retiring it as well. And then the cash is going to be here, cash is going to go down. So there’s going to be our transaction. We have the bond payable and discount going away which has to be the case if we’re retiring the bonds. The cash is going down for the early retirement. And we resulted in a loss in order for us to be able to retire the bonds early.

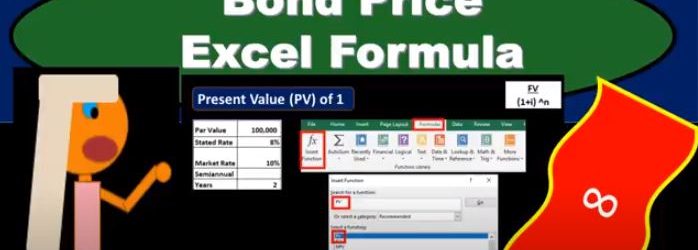

Bond Price Excel Formula

In this presentation, we will calculate the bond price explaining how this can be done using present value formulas within Excel. Remember that the bonds is going to be a great tool for both accounting and finance to describe the present value calculation. So that’s why it’s going to be used. Oftentimes It has two cash flows related to it, one’s going to be the face amount of the bond that’s going to be due at the end of the term of the bond. In our case, it’s going to be two years semiannual or four time periods. And the other is the flow of interest. So bonds are a great example because they have the two types of present value problems that we need in one area. So even if you’re not in an area where you’re dealing with bonds all the time, they’re still going to be used and useful to understand present value types of calculations. So here we’ve got the bond is going to have one cash flow of 100,000 at the end of four periods or two years, and we need to figure out what the present value is in order to price it back here at your at time period zero. And then we have these four payments in terms of the annuity 4000. And we need to take those and present value them, we could take each period and present value each payment and present value it. But the easier thing to do is to present value, an annuity when it’s applicable and present value, the one amount when it’s applicable. And therefore think of that about these as two basically separate cash flows that we’re going to have to present value separately. So we can do this multiple different ways. And it just depends on what you’re what tools you have. And where you are, in order to know how to do it. What you want to know is just that there’s different tools to do it. Anytime someone uses a different tool. What are they doing the same thing? And and when can you apply these tools and what’s actually happening here. So that’s what’s actually happening. We’re present valuing this information.