This presentation we will be discussing the direct write off method. The direct write off method as it relates to accounts receivable, quick summary of accounts receivable accounts receivable is a current asset, it’s an asset with a debit balance, we are going to be writing off certain amounts for accounts receivable that will become not due or not collectible at some point in the future. There are two ways to do this one is called the allowance method. The other is the direct write off method, we will be using the direct write off method here the non generally accepted accounting principles method being this direct write off method. However, a method that is typically much easier to use. Therefore, when considering whether or not to use an allowance method or direct write off method, we want to consider one do we have to use an allowance method due to the fact that we need to make our financial statements in accordance with generally accepted Accounting Principles, or are we able to choose between having an allowance method or direct write off method? If we choose to have a direct write off method, it’s probably because we’re thinking that the receivables that will be written off are not significant.

01:17

In other words, they’re non material to decision making. So if we had our accounts receivable here, that’s what people owe us. We want that on the books to represent the fact that we do have an asset. We do have people owing us this money. However, if there’s a significant amount that we believe will not be paid to us, then we want to note that if we don’t, we’re overstating our assets and we’re also distorting our net income on the income side of things. So the deciding factor then is going to be one do we have to use an allowance method that will be a general Accepted Accounting principle, if we have to make financial statements in accordance with a strict rule and generally accepted accounting principles? Then we would typically need an allowance method unless the amount was in material. If we’re not required to be recording our books with regard to the allowance method because of generally accepted accounting principles, the question then is, should we be recording the allowance method? Is it better for decision making that decision basically, again, coming down to whether or not it’s going to be material to decision making, how many of those receivables we believe will not be collectible.

02:29

As we go through the direct write off method, we always want to compare it to the allowance method to see the differences between the two methods. We have this account here this red account that will not be used as we go through this direct write off method but there to show us what would be there if we were to use an allowance method to compare and contrast as we go through this process. So first, we’re going to say that a customer CW is not going to pay off the accounts receivable of 9000 for whatever reason at this point, point in time, we’ve decided we’re not going to get paid. And therefore, we’re going to have to decrease our accounts receivable. And the decrease is going to be a credit to accounts receivable accounts receivable is a debit balance asset account, we’re going to do the opposite thing to it to make it go down because we’re not going to get paid. Therefore, our journal entry will be a credit to accounts receivable. That will be the same under the allowance method or the direct write off method.

03:25

The other side is what will differ under the direct write off method, we will write it off to bad debt expense. This is probably what seems most natural at this point in time, because it’s not getting paid. So we’re going to write it off to bad debt expense. What actually happened here? How did that accounts receivable get on the books in the first place? we debited accounts receivable and we credited revenue when we made the sale. You would think then that we would decrease revenue at the point in time that we discover that this sale $9,000 worth is not valid, we’re not going to get paid that $9,000. But we don’t typically reduce revenue one. And therefore we’re going to make this other account that’s going to kind of be like a contra revenue account because we never really earned revenue, bad debt expense. So it’s going to be an expense, we’re really kind of taking away revenue that we had recorded in the past.

04:20

Now, the problem with this method, of course, is that when we record this expense, we will be reducing net income at this point in time, when really the sale that happened that increased revenue happened in the past. So it’s a timing problem that we have not so good timing in terms of the direct write off method here. Let’s see, if we post this then we’re going to post this to the general ledger accounts here, then we’ll record it to the subsidiary ledger. So we’re going to say that the bad debt is going to go up is the general Ledger’s the two accounts. We’re not going to show all the accounts for the general ledger every account here on the trial balance would of course Have a general ledger accounts showing the detail by date. That means it’s going to go up from zero by 9000 to 9000. That’s going to be the new balance. Here the accounts receivable it started at 1,000,200. There’s the 1,000,200. What was 1.2 hundred before this, now we’re going to bring it down by the 9000 to 1,000,001 91. There’s the 1,000,001 91. Now on trial balance after this transaction has happened, we also need to record this to the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger.

05:32

So we know that c W is the individual that didn’t pay us. We note that the accounts receivable over here on the trial balance and here on the general ledger show who owes us money, how much is owed to us. The GL gives us detail but only by date. The subsidiary ledger would then give us detail about who owes us this money. We’re just going to show the account for CW here but in a subsidiary ledger we would be having all the accounts over All customers owing us money, and if summed up, then it would add up to the amount on the trial balance. So in this case, cw owes us that 9000, we’re going to say that they’re not going to pay us, we’re going to take it out of the subsidiary account, and that will bring it down to zero. Note the major problem and difference here between the two methods is that on this method, the direct write off method, we brought net income down by this 9000, we had revenue 378 minus 9000.

06:29

We just recorded bringing net income, the subtraction of those two to 3006 69 369,000. Under the allowance method, we would have recorded that through the allowance account that we would have already set up not decreasing net income at the point in time that we determined that something will not be due, but having already done so or estimating what the decrease will be trying to match up the bad debt expense to the revenue that it was actually incurred in rather than waiting until we determine when something is uncollectible note that we have a lot of control over net income in some ways, if we’re able to then decide when we think something that’s going to be a bad debt, because we can write things off at certain times or wait and not write them off, and that can have a significant influence on the net income.

07:22

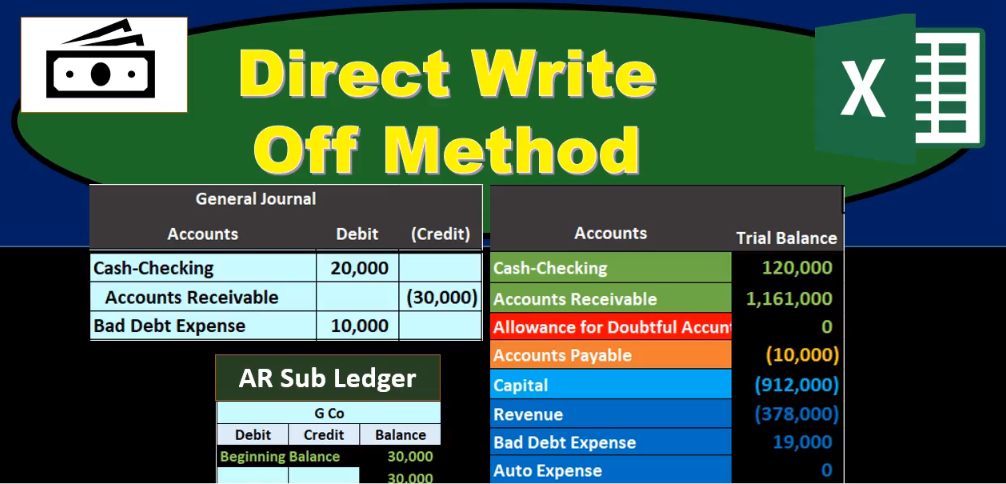

On the other hand, if we are forced to basically make an estimate of how much we think of this revenue will be uncollectible, then we at least have to give a guess as to what we think a fair number would be that would be uncollectible related to the revenue earned during this time period. Next transaction, we’re going to say that g company had a payment of 20,000, but owed us 30,000. In other words, of this receivable, this 1,000,001 91,000 g company owes us 30,000, but they’re gonna go bankrupt or something happened, we’re only going to get to 20,000 We’re not going to get the rest we can imagine they grow and bankrupt, we’re going to get 20,000. In the bankruptcy, the 10,000 is something that we’re not going to get, we’re going to write it off. Therefore, we can say, okay, cash went up just like a normal payment on account. Cash is a debit balance, we’re going to make it go up by doing the same thing too. It’s another debit 20,000, then we’re going to credit the accounts receivable.

08:24

The account here, of course, saying that they owe us money, it’s going to go down because they don’t owe us money anymore. This is a debit balance account, and therefore it goes down with the opposite of a debit or a credit. However, we’re not going to credit the 20,000 but the 30,000 the total owed to us so that we totally removed the amount that’s owed to us off the books. Our debits do not equal our credits. Now, we need a debit of 10,000. That then is going to go on to the direct write off method to bad debt expense. This is what will differ under the two methods and the direct write off If it goes to bad debt expense, under the allowance method, it would be going to the allowance for doubtful accounts. So this is going to be the same type of transaction we had before only difference being that we received a partial payment. So don’t let that throw you off. If you see a partial payment, then we still going to go through our normal transactions, we’re gonna say is cash affected? Yeah, we’re going to increase the cash, then just note that you have to take the receivable off, but not for the amount received, but for the entire amount because we’re not going to get the rest, therefore needing to remove the full amount owed by this cups customer.

09:37

So we don’t show that they still owe us 10,000. They don’t owe us anything anymore. Because we gave up on the other 10,000 then we have to decide how we’re going to even this thing out. We do so with another debit. If we then post this to our general ledger accounts over here and our subsidiary ledger, and then we’ll take a look at our Indian trial balance. We’re going to say that cash is going up from 100,000 by this 20. So we post that to the GL Account increase in the GL to 120,000. That, of course will now match our trial balance after we post that, then we’re going to say the accounts receivable, this 30,000. Credit, we had 1,000,001 91. Here, it’s going down by 30 to 1 million at 161. That then matches what will be on the trial balance, then the bad debt here, the thing that will differ the bad debt changing as we determine that something will not be collectible, going from 9000. Here’s the 10. Here’s the 10 going up by 10 to 19,000.

10:41

That been the amount in the bad debt on the trial balance. Note once again, that the revenue is going on well, the net income is going down bad debts going up is bringing net income down that’s going to be a difference that the major difference between the direct write off method and the allowance method. Under the allowance method, this journal entry would not be affecting net income. net income would only be affected when we make an estimate about what the bad debt should be not based on when it is becoming bad, but based on matching it to the revenue in the same time period. And we could do that with two different methods we’ll talk about in the later point. But remember that the allowance method should have a better matching principle between the revenue and the bad debt happening in the same time period. Then we have the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger. Remember that the accounts receivable here represents how much is owed to us but doesn’t give us any more detail than that.

11:45

The accounts receivable here gives us detail but only by date of transaction. We need the detail by who owes us money. That’s going to be the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger. We’re only going to look at this particular customer here, this customer GE company, but all the customers remember would be included in the subsidiary ledger, if we added up all customers, it would then add up to the accounts receivable on the trial balance. And on the general ledger, we’re going to say record the same thing as 30,000 and goes here. And that’s going to bring the balance down to zero. So that’s critical. We know that g company doesn’t owe us any more money, they paid us 20, even though they owed us 30, we took the entire 30 off the books, not leaving that 10,000 still owed to us because we gave up on it and therefore need to take the entire 30 off the books bringing them down to zero. Next transaction, we’re going to say received a payment from CW after writing it off. This is going to be a typical book type transaction not so typical when we have a real life situation because if we wrote off the bad debt, we totally gave up on it. So we gave up on the bad debt.

12:57

And then and that doesn’t normally happen until we Go through a pretty significant collection process. And then after we gave up on it, we’re not calling anymore, we’re not actively trying to collect on it, it then gets paid at some point in the future. How do we deal with that? That’s a great book question because it really emphasizes the difference between the two methods. And how are we going to kind of reverse this transaction? Now, this is gonna be the trickiest thing that we have here. Because typically, if we got paid, you would think that we would debit cash. And then we would credit what we are. We know we wrote it off to bad debt. So you would think, okay, I wrote it off the bad debt, I can just credit bad debt. So typically, we would go through our questions is cash affected? Yeah, I debit cash. And then the other side can’t go to receivable because I wrote it off. Well, where did we write it off to bad debt. So we could debit cash and credit bad debt. However, we’re not going to do that. And this is kind of an exception to the rule of dealing with cash. First, and that is because if we do that we bypass the accounts receivable.

14:05

And we don’t have a record showing us that in the receivable account in the subsidiary ledger for this customer that they actually paid it, what we want to do is put them back in good standing on the receivable account, and then write it off as we normally would. Therefore, we’re going to do this with two transactions two entries, we’re going to put them back on the books, we’re going to say the receivable is going to go back up, we wrote off the receivable, we’re reversing the write off. And then we’re going to put the other side to bad debt expense, meaning when we wrote it off, we credited the receivable to take it down. And under the direct write off method, we put the other side to bad debt expense. We’re just reversing that now. We’re going to put the debit to accounts receivable and the credit to bad debt just reversing the write off that happened because it didn’t really happen because they actually paid us so we gave up on them too soon. Now That this bad debt expense is part of the reversal. And part of the difference that would be between the two methods. Under the allowance method, this amount would have been written off to the allowance, and therefore would be reversed now to the allowance.

15:15

Once we do that, then the second piece is is easy because it’s our normal transaction, we got paid on account, the accounts receivable is back in good standing, therefore we’re gonna say is cash affected? Yeah, it’s a debit, we’re increasing cash with a debit, so the debit to cash and then we’re decreasing the receivable, which we just increased by 9000. So again, we could simplify this transaction, you can look at this and say, Hey, we’re duplicating information. I mean, I’ve got accounts receivable here, and I’ve got accounts receivable here, and it’s just doing the same thing. One’s being debited, one’s being credited, I could eliminate those two, we just eliminate these two we would be left with a debit to the checking account and a credit to the bad debt problem. problem once again, is that we want to see the paper trail in accounts receivable. We want to be able to go to the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger and say, yeah, this person paid us, we’re willing to do business with them in the future, we can’t see that. If we don’t reverse the transaction and then put it through the subsidiary ledger. Let’s take a look at recording this then we’re going to say first, the accounts receivable is going to go back on the books.

16:25

So we took them off the books here and the subsidiary ledger back on the books and the receivable increase in the amount to 1,000,170. Here, other side, and that in and that’s all it’s there right now, others have said, it’s going to go to the bad debt, that debt is being reversed here. So here’s the bad debt that we wrote off incorrectly, we gave up on it too soon. We are reversing it here at this point in time, bringing the 19 down by the nine to the 10,000. Then we’re going to record the second piece, which is just that Normal transaction for a receipt on account receiving money for the accounts receivable for something that we did in the past. So here’s the cash going up, here’s the cash going up. And that brings the balance from 120 to 129. And then the other side of it is going to be the accounts receivable here. It’s going to be the credit. Here’s the credit. So note what happened. We started before this process in the receivable General Ledger at 1,000,001 61. And then we brought it up, putting them back in good standing and back down to bring it back to that same spot. One line 160 1000.

17:39

We’ll see that same process in the subsidiary ledger, the subsidiary ledger for CW remember we had 9000 we gave up on them wrote them off, left leaving us at zero and then ignore those 9000. Here we’re at zero at this point in time, and then we have the other side of it is going to be a debit to the account. receivables so the accounts receivable is going up with this 9000 putting them back on the books. So we took them down to zero, put them back on the books at 9000, bring it back up to a 9000 balance that’s from this transaction. And then we’re just going to take it right back off the books for the accounts receivable for CW here so CW another 9000 bringing the balance back down to zero.

18:26

So if we look at the subsidiary ledger, remember that this would be a subsidiary ledger with every account for every customer. However, we’re just looking at CW subsidiary ledger, they had 9000 owed to us. We wrote it off in the past prematurely we should not have done so because this was still a good customer. They just paid late, very late apparently. And so we brought it down to zero and then we want to see that we put them back in good standing here so that we can see the paper trail bringing them back up to owing us 9000 and then we record they paid us if we look at this payment, then it still brings us down to zero, but we can look at this payment and say, Well, how did we get paid, and see that they actually gave us money. Whereas if we looked at this transaction, and we just left it here, and we didn’t record the other two, we would drill down on that transaction and say, well, they didn’t pay us. And that would probably stop us from doing business with them in the future.

19:17

We want to say they’re back in good standing, and they paid us here, therefore, we can still do business. In the future. Notes, the effect here is going to be on the bad debt, bad debt is now going down. And that’s going to be a difference between the allowance method and the direct write off method where the allowance account would be the account affected, there would be no effect to the net income or the income statement accounts at all, under the allowance method, whereas under the direct write off method, of course, that debt is affected, and it would then bring that debt going down, bringing net income up.