In this presentation, we will continue putting together a statement of cash flows using the indirect method focusing in on adjustments to reconcile net income to net cash provided by operating activities. So this is going to be the information we will be using, we have the comparative balance sheet, the income statement added information, we took this comparative balance sheet to create our worksheet. So here is our worksheet for two time periods. This is the difference we’re basically looking to find a home for all of these differences we have done so with cash, and we’ve done so with a difference in retained earnings. So here’s cash, here’s net income, the difference in retained earnings, we will have to adjust net income shortly or at the end of the problem. We’ll we’ll take a look at that we’ll make an adjustment for it. We’re going to now find the difference for all the rest of these. Also note that of course cash is going to be the change in cash will be our bottom line. Never we’re going to recalculate this But it’s nice to know where we are ending up at. So this is kind of like even though it’s at the top of our worksheet, that’s where we want to end up by finding a home for everything else. So now we’re going to take a look at the adjustments to reconcile net income to net cash provided by operating activities. So these are going to be those types of things that we look at the income statement, and we’re going to say that these are non cash activities, meaning income is calculated as revenue minus expenses. And the cash flow.

Posts with the net income tag

Statement of Cash Flow Indirect Method Cash & Net Income

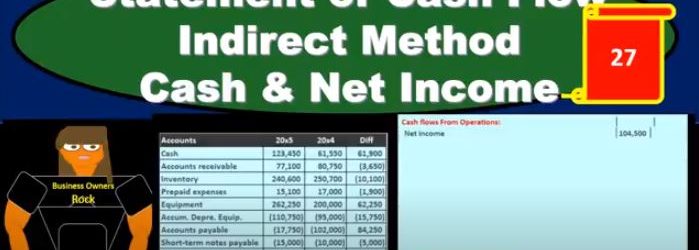

This presentation, we will start to construct the statement of cash flows using the indirect method focusing in on cash and net income. This is going to be the resources we will have, we’ll have that comparative balance sheet, the income statement, and we’re gonna have some added information. In order to construct the statement of cash flows, we’re mainly going to be working with a worksheet that we’ve put together from a comparative balance sheet. That’s where we will start. So we’re going to find a home, this is going to be our worksheet. We have the two periods. So we have the current year, we’ve got the prior year, and we’ve got the difference between those activities. Now our goal here is to basically just find a home for every component on this difference section. So that’s going to be our home. Why? Well, we can first start thinking about cash. What are we going to do with cash? That’s the main thing. This is a statement of cash flows here. So where are we going to put cash? that’s actually going to start at the bottom, we’re going to say that’s going to be our in numbers. In number we know it’s going to be cached. Now, we’re going to recalculate it. But it’s useful for us to just know and we might just want to put there, hey, that’s where we’re going to end up. That’s where we are looking to get. And now what we really want is the change.

Statement of Cash Flows Direct Method Vs Indirect Method

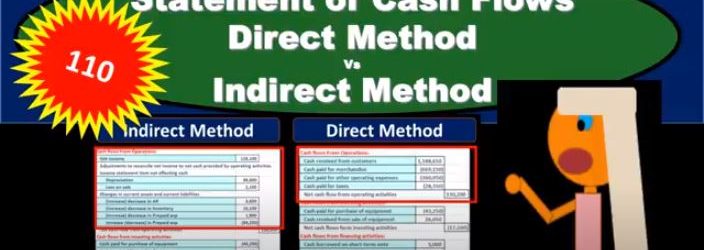

In this presentation, we will compare and contrast the direct method versus the indirect method for the statement of cash flows. It’s important to note that when we’re comparing the direct and indirect methods, we’re really only talking about the top part, the operating activities portion of the statement of cash flows. In other words, the investing activities and financing activities and in result will remain the same, we’re going to end up with the same result, which of course, will be the Indian cash that we can tie out to the balance sheet. And we’ll have the change of cash here, which is really kind of the what we’re looking for in the statement of cash flows. What’s going to differ is the operating activities, why are they going to differ? Why would we have the operating activities differ? Remember that the operating activities have to do with kind of the income statement you can think of it basically as the income statement being reformatted to a cash flow statement versus an accrual statement. So the income statement that we use is on an accrual basis, and we recognize that Revenue when it’s earned rather than when cash is received expenses when expenses are incurred rather than when cash is paid, that’s gonna be on an accrual basis.

Statement of Cash Flows Introduction

In this presentation, we will introduce the financial statement of statement of cash flows. When thinking about the statement of cash flows, we want to compare and contrast the reasons for it to what the other financial statements are providing us what information in other words, are we going to get from the statement of cash flows that’s not on the other financial statements, those being the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of equity, we’re mainly comparing against the income statement, because the statement of cash flows going to give us some similar information. It’s going to give us information over time, what’s happening over time, unlike the balance sheet, which is going to have a point in time. So we’re still looking at at timing what is what is going on over time. That’s typically our income statement, which measures performance. The major goal of the income statement is to measure performance, how have we done how much work have we done, revenue minus expenses, revenue being recognized when we earn the work when we’ve done the job expenses when we We’ve incurred something in order to help generate in the same time period. And that’s going to be the net income. What that doesn’t do, however, is measure cash flow. And when we first learn about the income statement, that’s going to be a real big distinction we want to look at, we want to say, okay, the income statements on an accrual basis.

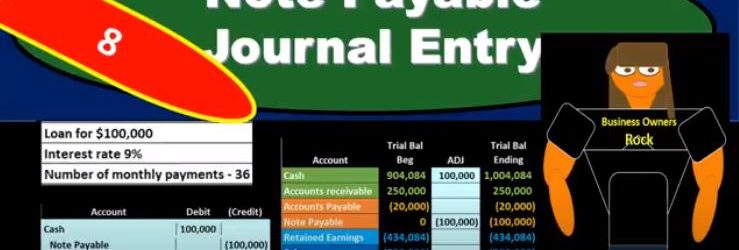

Note Payable Journal Entry

In this presentation, we will record the journal entry related to a note payable related to taking out a new loan from the bank. Here’s going to be our terms. We’re going to record that here in our general journal and then we’ll post that to our worksheet. The trial balances in order assets, liabilities, equity, income and expenses, we have the debits being non bracketed or positive and the credits being bracketed or negative debits minus the credits equaling zero net income currently at 700,000 income, not a loss, revenue minus expenses. The difficult thing in terms of a book problem, when we record the loan is typically that we have too much information and this is the difficult thing in practice as well. So once we have the terms of the loan, and we have the information, we’ve already taken the loan out, then it’s the question of well, how are we going to record this thing? How are we going to put it on the books and if we have this information here, if we have a loan for 100,000, the interest is 9%. And then the next number of payments that we’re going to have, we’re going to pay back our 36. Then how do we record this on the books? Well, first, we know that we can ask our question is cash affected? We’re going to say, Yeah, because we got a loan for 100,000. That’s why we got the loan.

01:14

So cash is a debit balance, it’s going to go up with a debit, so we’ll increase the cash. And then the other side of it is going to be something we owe back in the future. And that’s going to be note payable. And that’s as easy as it is to record the initial loan. The problem with this the thing it’s difficult in practice, and in the book question is that we’re often given, of course, the other information, like the interest in the number of payments, and possibly more information that can cloudy up the what we’re doing, and the reason these are needed, so that we calculate interest in the future, but they’re not really We don’t even need that information to record the initial loan. All we need to know is that we got cash and we owe it back in the future. And you might be asking, Well, what about the interest we owe interest in the future as well? We do, but we don’t know it yet. And that that’s the confusing thing interest, although we we will pay interest and we know exactly how much interest we’re going to pay in the future. We don’t owe it yet. Why don’t we owe it yet? Because we’re going to pay back more than 100,000. Why don’t we Why don’t we record something greater than 100,000? You might say, because we know we’re going to pay more than 100,000. And that’s because the interest is something that it’s like rent. So we’re paying rent on the use of this 100,000. And just like if we if we had a building that we rented, that we’re using for office space, we’re not even though we know we’re going to pay rent in the future. We’re not going to record the rent now. Because we haven’t incurred it until we use the building.

02:41

So the same things happening here. We know we’re going to pay interest in the future we’re no we know we’re going to pay more than 100,000 but it hasn’t happened yet. We haven’t used up we haven’t gotten the use of this hundred thousand and therefore haven’t incurred the expense of it yet. So the interest and is something we need to negotiate when making To turn off the loan, but once the loan has been made, and we’re just trying to record it, it’s not going to be in the initial recording. It will be there when we calculate the payments need and the amortization table. So the initial recording is pretty straightforward. We’re just going to say okay, cash is going to go up by 100,000. And then the notes payable is going to go up from zero in the credit direction to 100,000. So what we have here is the cash increasing the liability increasing, although we got cash, there’s no effect on net income because we haven’t incurred any expenses. We’re going to use that cash most likely to pay for expenses possibly or pay for other assets or pay off liabilities in order to help us to generate revenue in the future. But as of now, we’ve gotten we increase an asset and we increase the liability

Bond Retirement

In this presentation, we will discuss the journal entries related to the retirement of bonds. the retirement of bonds just means that we’re going to pay off the bonds in some form or another at some time or another, meaning the bonds are going to go away. Typically, that’ll happen at the maturity date at the end of the bond. So for example, if we have a bond on these terms, with the face amount of 240, the issue price of 198 for 80, for 15 year bonds, they’re going to be semi annual. What would happen is when we put this on the books, we would put it on the books as cash we got for the 198, the bond payable on the books for 240, and then a discount. And then of course, over the life of the bond, we would be paying interest for that 15 year time period two times that’s 30 payments. And then at the end of this we would also be be amortizing out the discount to get rid of it, to make it go away to the interest and then By the end of this time period, the discount would be zero. And we would only be left with a bond on the books. In other words, at the maturity date, we would have something like this on our trial balance, the discount is now zero. And the bond is on the books at 240, which is the face amount of the bond, if it were a premium, it would be it would be the same in that we would be left with just the bond amount and the premium would be gone to zero. And now it’s just like anything else that we don’t have to deal with interest at this point or anything else, we just need to close out the bond. And so it’s just like any other liability, we’re just going to pay at the maturity date. That’s how we’re going to retire it. So this is a 240 credit, we’re going to make it go down by doing the opposite thing to it a debit, and we’re going to pay cash, cash is a debit balance, we need to make it go down. So we’re going to credit cash. So this is going to be our journal entry. We’ll debit the bond make go away, and then we’ll pay off the cash. When we post this then the bond payable will be here. Here, it’s going to go it’s a credit, we’re going to debit it, making it go away to zero, and then the cash has a debit balance, we’re going to credit it making the cash go down. So it’s a pretty straightforward journal entry.

02:12

The only confusing thing about this journal entry is that it happens at the end of the bond term. So when we’re talking about book questions, we often don’t get asked it because usually we’re concentrating on how to calculate the interest how to calculate the face amount of the bond, how to record the bond, how to amortize the the bond, discount or premium. And we don’t really typically get all the way to the end of the bond, the retirement the maturity date, to record the end transaction oftentimes, and it’s a pretty easy transaction if we were to do so. And it’s a lot easier to if we can actually see the trial balance. When you see the trial balance, you say, oh, there’s a liability there. We’re going to pay it just like we would if it were note payable at this time. It needs to go down and then we’re going to pay it off with cash. Now it is possible for us To have a callable bond that we’re going to retire before the end of the bond date before the maturity date. So in other words, in this case, we have the bond on the books of 240,000. And we have the discount of 338 748. And therefore, if we were to calculate the carrying amount, we’d have 240,000 minus 238 748, or two a one 252. This 201 252 is the carrying amount of this bond payable. This is something that we owe in the future. If we can pay it off at this point in time for some cash that’s going to be less than this amount, then we’re going to have a gain resulting in a gain. And if we are paying it off early for something more than this, we’re going to have a loss. So let’s see what that’s going to look like.

03:52

The gain or loss can be confusing here. When we’re talking about a bond. It’s easier to get to that point by just doing the journaling So if we have all this information, especially if we have the trial balance, because then we can see what accounts are debited and credited on the trial balance or which accounts have a debit or credit balance, then it’s a lot easier for us to construct the journal entry. So the first is going to be given to us, we’re going to say that the cash that we’re paying is 230,000. That’s gonna have to just be given in the problem because that’s the callable price that’s how much we’re able to purchase these bonds for. So cash is going to go down because remember, we are buying them back basically, or we’re we’re paying them off early before the maturity date. So it’s going to be 230. Then we’re going to say that the bond payable has to go off the books. Now the bond payables on the books at 240,000, we can see it’s a liability, it has a credit balance. So to take it off the books, we do the opposite thing to it, a debit for whatever it needs to be to make it go to zero, the discount. Same thing we need to do whatever we need to do to make it go to zero because it’s Gotta go away. So when we construct the journal entry, we just know that we just got to do whatever we need to do to make it go to zero. If you have a trial balance in front of you, that’s easy to do, because we can see the discounts on the books at a debit. And we need to do the opposite to make it go down, which is a credit. If you’re looking at a book problem that doesn’t give you a trial balance, and just tells you that the bond is on the books at a discount, then you got to think through it. And one way to think through it might be to say, well, the bonds is a liability, it must be a credit, that discount means that we’re making the bond go down, because it must be decreasing, we’re having it less than the state, the face amount, the sticker price.

05:40

And since it’s a credit, the thing that makes a credit go down would be a debit. So that discount must be a debit because these two are really combined together. And a discount means that we we really the net of the two are below the face amount price, so this must be a debit. So if it were a premium, then this amount be increasing or greater than the face amount, and it would be a credit normal balance. Once we know that this is a, this is a debit normal balance for a discount, then we can do the opposite thing to it to credit it to make it go down. And then of course, we just need to figure out what the difference is we’ve got credits of 230,038 748 minus the 240. Debit means we need a 28 748 debit. And that of course, in this case, I’m going to say it’s a gain loss account here because it could have gone either way. But if it’s a debit here, then it’s on the income statement. That’s going to be a loss. And you just got to basically start to be able to recognize that why would that be a loss? Well, you can think through that. We paid 230 versus the carrying value, or you can also just think well, if it’s a debit on the income statement, It’s acting more like an expense, meaning expenses have debit balances, they go up in the debit direction, and they bring net income down.

07:08

Revenue has a credit balance, it brings net income up. This is acting like a, an expense because it’s a debit balance. If we debit the income statement, it’s going to make net income go down, that means it must be a loss rather than a gain, which we would think would make net income go up. So the other way we can think about this is to is remember, the carrying value is going to be the 240,000 minus the 38 748. So this is kind of a value that we owe on the bond. And it’s a liability, that’s kind of the value we owe and we paid more than the value that we owe. So that’s going to be a loss in this case. And that’s another way you can think through it being a loss. So if we post this out, then we’re going to say that the gain or loss 28 748 Here, making the income statement accounts go up, kind of like an expense bringing net income down. The bond payable will be posted here, it’s going to make the bond payable go to zero. That’s why we are retiring. It’s making it go away. And then we’ve got the discount, it’s going to make the discount go to zero because we’re retiring it as well. And then the cash is going to be here, cash is going to go down. So there’s going to be our transaction. We have the bond payable and discount going away which has to be the case if we’re retiring the bonds. The cash is going down for the early retirement. And we resulted in a loss in order for us to be able to retire the bonds early.

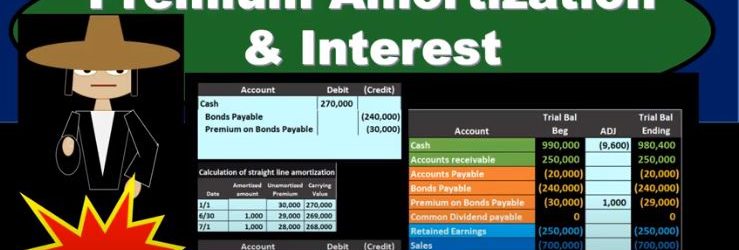

Premium Amortization & Interest

In this presentation, we will discuss the amortization of a bond premium and the recording of interest expense on bonds. This is going to be our starting point. This is the initial transaction in order to get the bonds on the books. Here’s our data down here we’ve got the number of years we’ve got the face amount of the bonds, we’ve got the issue price 270, we see that the interest on the market rate is different than the contract rate. The result then is that cash is going to be increased by the 217. The bonds payable went on the books for the face amount of the bond, the amount that’s on the bonds of the 240, which is a liability. And then we have the premium being the difference increasing the premium here by the 30. The 240 plus 230 is going to be equal to the 270,000 carrying amount book value of the bonds. Now we’re going to go through the process of recording the interest we can see that this is going to have 15 years bonds, we’re going to pay the bonds semi annually. So we’re going to have to record the interest on them. And we’re gonna have to reduce this premium in some way as well. Remember, at the end of the bonds, we’re not going to pay back the 270. We’re only going to pay back 240. So how are we going to get rid of that the premium on the bond and why are we going to do it in the way we will. We’ll start off by amortize in the premium using a straight line the method. Note that the effective method is the preferred method for amortize in a premium for generally accepted accounting principles, but the straight line method will be appropriate in some cases, if the difference is going to be a non material. And the straight line method is a simplified method and it’s easy for us to see what is going on. So we’ll start off with the straight line method.

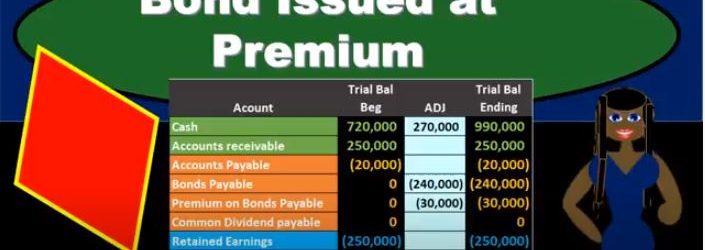

Bond Issued at Premium

In this presentation, we will take a look at the journal entries related to issuing a bond at a premium. When considering the journal entry for a bond, remember what can change and what is the same for a bond. When we think about a bond, it’s already been printed, we know the amount of the bond, the interest on the bond, the maturity date of the bond, these are already set. So if we’re making a negotiation with the bond after it had already been printed, then we can’t change the face amount. We can’t change the interest due dates. What can we change in order to negotiate and make a sales price on the bond, we can change the amount that we issue it for. So keep that in mind. Whenever you think about these bond problems. That’s the thing that’s going to differ from a bond to a note. The thing that changes when we want to loan is the interest rate. The thing that changes when we want to issue a bond that’s already been made is going to be the amount we receive For the bond being different than the face amount of the bond if there’s a difference in the market rate and the contract rate. So in this example, we’re saying that we issued a bond. Now note that when we think about the issuance of the bond, just like a note, we often have more information than we really need. And that can be a little bit confusing for us.

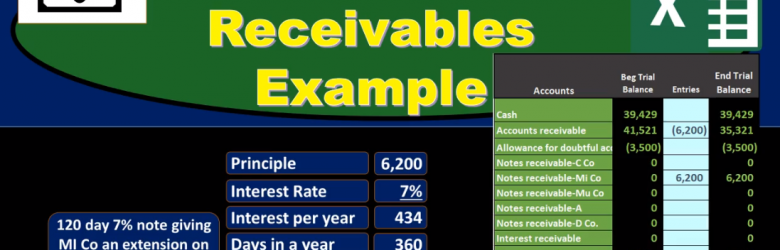

Note Receivable Example

In this presentation we will discuss notes receivable, giving some examples of journal entries related to notes receivable and a trial balance so we can see the effect and impact on the accounts as well as the effect on net income of these transactions. first transaction, we’re gonna have 120 day 7% note giving the company EMI and extension on past due AR or accounts receivable of 6200. When considering book problems and real life problems, one of our challenges is to interpret what is actually happening what is going on, which party are we in this transaction in? Therefore, how are we going to record this transaction when we’re looking at notes receivable? A common problem with notes receivable is the conversion of an accounts receivable to a notes receivable. So in this case, that’s what we have. We have an accounts receivable here that includes an amount of Due to us by this particular company in AI so these are our books, we have a receivable people owing us money for prior transactions goods or services provided in the past and they owe us in total, all customers owe us 41,521 this customer in particular owes us 6200 of this amount in the receivable that could be found not in the general ledger which would give backup of transactions by date.

Allowance Method VS Direct Write Off Method

In this presentation, we will take a look at a comparison between the allowance method and the direct write off method. When considering both the allowance method and the direct write off method, we are considering the accounts receivable account. Remember that the accounts receivable account represents some money that is owed to the company, typically from sales made in the past, on account haven’t yet received the funds for sales made in the past and therefore, the company is owed money. We see this amount on the trial balance in this case 1,000,001 91. We then want to know information about that, including who owes us that money. We can’t find that typically in the GL as we have a GL for every account the GL only giving us the information by date. Typically, we want to see that information also broken out in the subsidiary ledger saying who owes us this money.