Corporate Finance PowerPoint presentation. In this presentation, we’re going to continue on discussing the income statement. Get ready, it’s time to take your chance with corporate finance income statement continued. Remember that as we think about the financial statements, we can break them out into basically two objectives that an investor might have the investor would want to know two general things one, where does the company stand at a point in time with their approximate value as of a point in time? And two? What is the likelihood of their performance in the future? What how well, will they do in the future? How can we predict how well they will do, we’re going to base it on past performance. So the point in time statement is going to be the balance sheet. So remember, if you’re looking at financial statements, for the year ended, say, December 31, the balance sheet will be as of a point in time and therefore as of December 31, it will not be a range. Whereas if you’re looking at a time frame, meaning the beginning to the end of the period, so if you’re looking for financial statements for the period ended, or the year ended, December 31, then the income statement, the primary timing statement, will be represented, it’ll say January through December or for the year ended December 31.

Because you need the full range of time in order to be recording the income statement, because it’s a performance statement. It’s just like trying to say, how many miles did we drive in an hour? Right? How many hits did a batter get last season? Why do we want that information? It’s not because it’s going to tell us, you know, we already know where it got us to, if I know how many hits, you know, were taken by a batter last season, where did that get them? Well, it got their team to wherever it got their team, right that wherever they ended the season off at? What did the income statement do? What did our revenue and expenses do last year? Well, it got us to whatever point in time is at on the balance sheet, you can take a look at the balance sheet and see where that got us. The point isn’t to see where it got us last year, per se, it’s to say, How far did we go from the beginning to the end of the year, because that will give us some predictive power in terms of what we believe will happen next year. And that’ll help us to make decisions next year. So this is the performance statement. Now the other statements here, the statement of retained earnings is kind of kind of tied together the income statement and the balance sheet. And then we got the statement of cash flows, which is another performance statement, but it’s going to be kind of our think of it kind of outside of these two. In other words, these two would be prepared first on an accrual basis, then we would go back in and kind of reform it on a cash basis to see the performance or the flows on a cash basis method. So here’s the financial statements that we have, we got the balance sheet we looked at last time, that’s where we stand assets equal liabilities plus equity assets is what the company has liabilities and equity or who have claimed to it two sides to the coin, noting You can also write that as assets minus liabilities equals equity, meaning equity here would be like the book value of the company, the balance sheet is where we stand. So if we’re talking about financial statements for the year ended December, the balance sheet is as of that point, December not for the entire range, then the income statement is going to be related to the balance sheet. In that it’s going to tell us how did we get to this point? How did we get to in essence, assets minus liabilities, in this case of the 1,220,000, it’s not going to tell us the whole story, it’s going to tell us last year one years of the story, just like a baseball, you know, we can look at the how many hits someone got last season, that’s not their lifetime, that’s basically last season. So that’s going to be what we have here last year’s performance. And that’s going to be the income statement, the bottom line of the income statement is going to be net income. And then we can break out that net income to basically earnings per share. And if we have preferred stocks, that’ll muddy up the water a little bit, so we’ll get into that shortly,

03:58

then what’s going to tie these two things together is going to be the statement of retained earnings. So the statement of retained earnings are linking these together how because the statement of retained earnings is going to link where we started at the beginning of the year meaning the balance sheet as of the end of last year to where we ended up at the end of this year. What’s the linking factor we’ll we’ll have the beginning balance, then we will add to it the net income or in this case, the earnings available to common stockholders, which we’ll talk about shortly, and then how much money was distributed out in the form of dividends to get us to the retained earnings that will be then on the balance sheet. So these two things are linked. So remember that they are linked and you want to think about these two statements as basically part of the accounting equation, part of the same thing. Then the statement of cash flows I would think about that basically separately basically taking and you can imagine the process of putting these financial statements together first doing the balance sheet income statement statement of retained earnings, then taking that information reworking it in such a way that Were in a cash basis as opposed to an accrual basis so that we can see the flows performance not measured by accrual standards not measured by when revenue was earned and when expenses were incurred, but rather by when cash flows came in and left the company. Okay, so the income statement performance statement, it measures profitability, that’s what the income statements gonna do. It’s gonna cover the time frame. This is a common question that you’ll get all the time. And, you know, the beginning, you know, one of the basic first questions is the balance sheet. Is it a point in time, or is it a timeframe, income statement point in time or timeframe. Income Statement is a timeframe, meaning it has a beginning of the period to the end of the period. So if it’s a year ended, it’s from January to December, you have to have a range of time, in order to talk about how much revenue you have earned, because it’s a matter of performance. So it can can be presented in a single step or multi step state us statement. We’ll talk a little bit more about that when we get into the financial statement. But you can represent the income statement very simply to summarize the data or more complex Lee in order to hopefully provide more data without completely overwhelming the reader of the financial statement. So we have multi step format will be the best for analysis, we, if we’re looking at it from a corporate finance standpoint, or an investment standpoint, we’ll typically want the more detailed multi

06:21

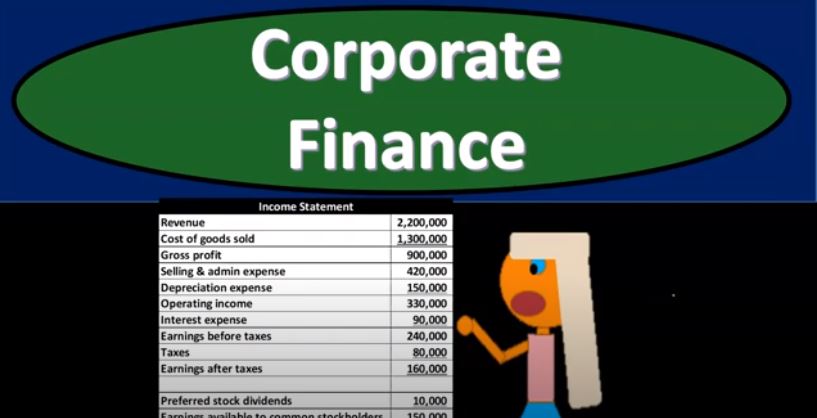

step income statements so that we’ll have more subtotals, on which we can perform analysis. So the income statement categories, if we break them down into like components of the income statement, this will make more sense when we actually look at it. But the income statement can be one of the longest statements we look at, which means it can be intimidating to Pete for people to look at. But if you just think about it as its components, it’s not that it’s not that it’s pretty basic item. And really, you can think of the income statement as basically two categories of item one revenue to expenses. So revenue minus expenses is net income. But then we have these subcategories that we will typically break out. Now these are the subcategories we will be working with. In this course, you might see what we’ll have different names that we’ll take a look at here, but you want to get the formatting of it down, and then you’ll you’ll be able to apply it even if even if they use a different kind of format for it. So we have the gross profit, you can you can abbreviate it as GP gross profit, that’s going to be the sales, which oftentimes is what we call the revenue account, sales or revenue or income, minus the cost of goods sold. Now Cost of Goods Sold will be there, if we sell inventory, if we sell things, then the cost of goods sold represents the cost of the inventory we’re selling. If we don’t sell inventory, then we’re not going to have a cost of goods sold. But if we do sell inventory, then the cost of goods sold is going to be one of the most important costs or expenses that we have. Because it’s going to be the largest typically, because the cost of the thing that we’re selling is usually the largest expense that we have. So we want a subtotal there to get us to the gross profit, we’re going to have another component, which will be the earnings before interest and taxes, which you can abbreviate as EBIT, or otherwise known as typically the operating income op. And that’s going to be the gross profit where we left off this time minus the operating expenses is going to be the expenses for basically, the operation, meaning we’re going to have the expenses, but we’re going to stop short of those expenses, such as interest and taxes that are going to be outside of operating expenses, and we’ll discuss that more in a second, then we have another category that’s going to move on from there, that’s going to go to the earnings before taxes, which we can say EBT interest shorten that that’s going to be the operating profit where we left off last time, minus the non operating expenses, such as the interest expense that we’re going to use, that’s going to be our typical format that we will be working with here as we do the analysis. And that’s and then we’re going to basically account for the taxes, which means we’re gonna have the earning after taxes or otherwise known as net income, which is going to be the earnings before taxes, minus the taxes to give us the net income. So let’s take a look this will be the standard format that we will be working with a lot of times in, in this course. So you want to get used to the standard format, it should it should fall in with most income statements. But again, you might have different kind of naming of the categorization. So what I want to break out here is Note that you can represent the income statement very simply as just basically revenue minus expenses in a single step income statement, which could be sales minus expenses, revenues, minus expenses, whatever they’re calling the top line, categories wise it would be revenue revenue is is basically the earnings of the company. Expenses are what has been consumed in order to earn the revenue. Now, of course, you can take revenue minus expenses, and that would give you the net income. And that would be fine. You could you could do that. That would be a single step type of income statement, but it wouldn’t give you as much detail as you want right. Now what you want is some more categorizations on On the types of expenses you have, and and the types of revenue, if you have different types of revenue, so then you’re basically going to be breaking out those components. So, most of the time on an income statement, notice, you’re typically only going to have one income statement account or both, or a couple income statement accounts. Why? Because that the point of a business is that they specialize in what they do well. And so the type of things they do to generate income will be somewhat limited, because that’s what they’re doing. They’re specializing to earn that, that means that everything else that they need in order to operate the business is what they’re going to pay for. And that’s going to be the expenses, therefore, the expenses will be, you know, vastly longer in categorization, then the revenue. However, in total dollars, of course, the objective is through specialization in this one task, we will generate more revenue coming in, then the expenses, it took us in order to generate that revenue, even though when thinking about the kinds of things we are doing, we’re doing only basically one thing with regards to the earnings of revenue, whereas we’re

11:08

paying for a whole bunch of things, and thus many more expense accounts than revenue accounts for the money that is going out in order to help us generate that revenue. So when you think about the income statement, notice revenues the major, you know, performance statement, that’s the goal of the company. So in other words, all the expenses everything below revenue is basically going to be an expense. And why are we Why are we Why are we using those expenses? Why are we consuming these things in order to help generate revenue? So the purpose of the income statement is revenue generation at the top here? And then you can also even pull this to the balance sheet, on the balance sheet, the assets? Why do you have the assets on the balance sheet? Because they’re, they’re there to hopefully help us generate revenue in the future? Why are those assets? Not basically on the income statement? Why are they not expenses are something on the income statement, because we haven’t consumed them yet, in order to help us generate revenue? They’re on the balance sheet, because we expect to consume them in the future, in the earning of revenue in the future. Why do we have liabilities on the balance sheet, because we wanted to finance the purchasing typically, possibly of assets, such as property, plant and equipment and other assets, so that we can earn revenue in the future typically, right, and that’s gonna give us assets minus liabilities is equity. So the revenue is basically our objective of what we’re doing, we’re looking to generate revenue, everything underneath that on the income statement are represent expenses, expenses are things that we have consumed within the same time period, in order to help us generate the revenue in this time period. So then we’re going to break that those out into their components. The biggest component, if we actually sell things will be cost of goods sold, the cost of goods sold, represents the inventory that we sold. Now, if we don’t have inventory, again, we won’t have cost of goods sold, it won’t be there. But if we do have inventory, then the cost of goods sold is going to be the biggest cost typically, because it represents us consuming something in order to generate revenue, not cash, because we didn’t pay the cash. When we sold the inventory, we paid the cash prior to put the inventory on the books as an asset. Then when we sold the inventory, we consumed the inventory, meaning we gave it away in order to generate the revenue. So the cost of goods sold is us basically recognizing the decrease in the inventory, the cost of the inventory, in order to help us generate revenue. Now these two things will typically move in the same kind of way, because if revenue goes up, you would think that we sold more units of income inventory, and therefore the cost of goods sold would typically go up in proportion. If revenue goes down, we would typically sell Cost of Goods Sold less cost of goods sold or less inventory, meaning Cost of Goods Sold would go down in proportion. If we if we subtract these out, and you got revenue minus cost of goods sold, the that gives us what we call gross profit. Now, gross profit is just a stopping point along the way, we could have just kept on subtracting all other expenses. But we want to stop at gross profit. Because that’s going to be a nice useful subtotal for us to do ratio analysis on which we’ll look at later, then we’re going to be grouping out these selling and admin. Now these are really expense categories that we have selling and admin expenses, you can call them, they’re typically going to be period costs, that you might you might call them, and they break out. So you might see these in two categories selling and then admin. And then within those categories, the actual expenses underneath them. So for example, selling expenses would basically be anything if you think of the administrative office as different from the sales office. So you have a store, let’s say we sell guitars, if you have the administrative corporate office, they don’t sell anything there. That would be the admin section and then you’ve got the store. That’s where we sell everything. You would think Thank you. expenses related to the store then would basically be the items under the selling costs. So that could be the sales, the salary of the salespeople or the or however, they’re paid the hourly rate of the salespeople possibly, and whatnot. And it’s going to be anything in the store, the maintenance, possibly of the store and whatnot, could be in the selling category. And then the admin category. If you’re thinking about the corporate office being its own place, that’s where all the administrative the executives work and whatnot, those are going to be an administrative costs and things like salary expense for the admin and maintenance of the facilities related to the administrative expenses, the office building, would basically be an admin. Now in nature, note that these costs are often fixed in nature, meaning, the cost of goods sold, as we said, will go up and down with the the sales units that we will have,

15:54

the selling and admin typically will will include things such as, such as rent, such as salaries and whatnot. So it’s more likely that the many of these costs are going to be more fixed, meaning such as the rent, if revenue goes up, for example, that doesn’t mean we’re going to pay more rent, the rent will be the same unless we had to, you know, purchase more property for revenue increase, right? If If revenue goes up or up, we’re not going to pay more salary, unless we give someone a raise or something because the salary is fixed. If revenue goes down, same thing, we still have to pay the same amount of rent, even if we’re even if we’re using the facilities less, then we’re gonna break out depreciation. Now depreciation could be in selling an admin as well a component of selling an admin meaning depreciation represents the use of property, plant and equipment, we’re going to allocate the cost over time, we’ll get into this more, I won’t get into a lot of detail here. But it represents, like a deviation from an accrual basis and a tax basis. So we want to pull that out. So we can see it specifically on things like the statement of cash flows. So notice, we’re going to break out the depreciation typically, in our example, problems, but just know that you could have depreciation under selling and admin, for example, depreciation on the sales store would be under selling and depreciation on the office building where the admin work would be depreciation, typically under the admin category. So these are going to be other categories of expenses, these are going to be our operating expenses, these are the things we have to do normally, period to period, we have to do these, and these are part of our normal operations. So we’re going to then take our subtotal of gross profits, and now we’re now we’re going to just subtract the expenses along the way, it’s always going to be expenses, we’re not going to record a new revenue, generally, down here, at you know, it’s usually just gonna be revenue minus expenses. So we will subtract the 900,000 minus two 420, minus the 150 gives us to the operating income. Now, operating income is going to be a subtotal, it’s useful, because that represents the income from our normal type of operations. So so this is the thing that you would compare to next period, which you would think would be somewhat standard. Because next period, we’re gonna have, you know, whatever sales we have, we’re gonna have this cost of goods sold is going to be, you know, doing the same type of thing you would expect, we would still have the selling and admin, because that’s part of our operations, the sales people and the admin people. And the depreciation related to it would be part of those normal operations. Again, remember that the selling and admin, if broken out into categories can start to get quite long, because you might have selling expense, and then a whole bunch of expenses that would be allocated to the expenses related to the sort store, admin expenses, and many of the in a whole bunch of expenses allocated to admin. So we’re kind of summarizing those, those two groups, if you were to break them out, the income statement can get quite long. But just realize we’re just, we’re putting all that into into one category, they all fall into, basically, you know, that category of expenses that would give us then the operating expenses, the expenses for normal operations. Now, we want that subcategory, so that we can list things that are not part of the normal operations, which might include things such as financing, why isn’t financing part of normal operations, because financing has to do with basically we needed a loan in order to help us you know, buy, buy something, buy assets, or whatnot in order for us to do our normal operations if it wasn’t for the fact that we needed the loan. In other words, if we financed the purchase of equipment or something like that, instead of by alone in some other means, then we wouldn’t have you know, the interest expense. The interest expense isn’t part of the normal operations. It’s it’s a function of the financing that was needed. So we want to give more

19:42

information to the reader by breaking that out separately, saying hey, look, this is this operating income is related to our operations, the interest expenses related to financing, and break out out in a separate kind of component. And you might have other kind of less common type of things that that are One time, things that aren’t expected to repeat that that might be broken out as not normal operating activities. But we’re going to be working mainly which is interest expense here. So now we’re going to take our last step total operating income, minus the interest expense gives us our earnings before taxes. So this would basically be our net income, our bottom line, if it weren’t for the fact that we then have to pay taxes, and you have to pay in the US got to pay federal taxes, income tax, if you’re a corporation, if you weren’t a corporation, then then the taxes would flow through. And that’s a different story. But Corporation, you’re going to be paying tax on the corporate level, and you might have state tax that you got to pay to, and you might have other, you know, types of income stack taxes for if you’re if you’re multi national company or something like that, right. So we got to add up all the taxes. So we’re going to take our earnings before taxes, and then we’re going to figure the tax on it. And we almost have to break that out. Because the taxes if we’re talking income taxes, which we are now will go up in proportion to our taxable income. Now, this gets a little bit confusing, because when you calculate the taxes, you might say, hey, look, I can’t calculate the taxes on earnings before taxes, because that’s book earnings. And if I look at the tax return, it gets more complex than just you know, you got to you got to get tax earnings, which are going to be different, you might have to deal with credits and whatnot, that could muddy the waters and make things a lot more confusing. Note that in practice, what will happen is you’re going to figure out, you’re going to do a calculation to estimate the taxable income or a rate that you can apply to the book value. And we won’t get into that calculation on it. In advanced financial accounting, we talk about that if you wanted to see how they come about that calculation, but in essence, they’re trying to approximate what the income tax rate would be that they could then apply to the actual book taxes. So if that, that used to bother me when I have. So in any case, if then if you subtract these two out, that’s finally going to get you to the bottom line, which could be net income, or earnings after taxes. So top line revenue, bottom line is going to be you could think of as net income typically will be called or earnings after taxes. So this is how much we have brought in in terms of revenue, earnings after taxes is the net income after considering all the things that we had to consume, in order to generate that revenue in the same time period in the same year, if we’re talking about one year time frame. Now, you might see then, at the bottom of the income statement, we could say, okay, that’s the earnings. Let me try to break that earnings out. By Owner chunks by shares, I want to I want to see that earning and see if I can break it out by shares. So if we’re if we’re an investor, and we’re thinking about, we want to break it down by units, so then we can think about how many units we have. And since the corporation is broken down into standard units, we can do that. Now, if you have pervert if you have preferred stocks, it’s going to kind of muddy up the waters a bit. Because note that if you have and not all companies will have preferred stock that will that will be there. But if you have the preferred stock, typically that means that the preferred stock has claimed to some of the earnings before the earnings are then distributed to the common shareholders, which are typically considered the owners. That preferred stock amount, though is typically fixed, and typically will not change then as revenue or increases. So if you So in other words, if you owe the preferred stockholders 10,000, if you were to declare a dividend, you would have owed them 10,000, whether or not you had 160,000, earned or 300,000. That was earned, right? Because their amount that they’re they’re owed is fixed. So the benefit is that they get paid first, once you distribute the dividend, typically, but the drawback is that the amount is fixed. So if revenue happens to go up, it won’t, it won’t. And but and then, and they also don’t have voting rights typically. So then that 160 minus what you got to pay to the to the preferred stockholders, if you give a dividend gives the amount that would be available to the common stockholders, which would be the 150,000. So the 150,000 now is what’s going to go to what we would typically think of as like the normal owners, the people that have voting rights in the stock, and that would be the 150. Now, once again, note that that if this 160,000 went up to like 300,000, then the preferred stock would still only get the 10. And then and then the common stockholders would get the difference, meaning the common stockholders would benefit from an increase in the revenue. Whereas if this went down, if it went down below 10,000 to like 5000,

24:38

then you’d have to pay the preferred stockholders first, and the common stockholders would get nothing. So you can see how the preferred and common are not preferred doesn’t mean better. In essence, it means it’s preferred and that it’s going to get paid first. Generally, there’s pros and cons to either of them. So then, if we if we take the 150,000 that’s going to be allocated to the common stockholders and divide it by the The number of shares that are outstanding, the standard units that are outstanding divided by 1.25, we then we can we can then get, let’s do that, again, 150,000 divided by 120 is going to give us the 1.25. And that’s what we call the earnings per share. Now, the note that the earnings per share doesn’t mean that they’re gonna, that the earnings per share are actually going to be given to the owners, the owners don’t actually have access to that to that dollar 25 per share. Also note that that the fact that we have 120,000 shares outstanding, does not represent the fact that we have 120,000 owners outstanding, because one owner can own multiple units of the company, just as one person can own all multiple dollars, which means which are multiple units of valuation. So that means that we, you know, if you own if you if you own, if you own 10,000 shares, you’d multiply this times 10,000. And you’d say that your your value, then for earnings per share allocated to you would be that, that 12,500. Now, note that you’re not going to get that money necessarily, right, and you have no way of doing that, as an owner, that doesn’t have a significant influence in the company, meaning I don’t have enough shares to basically significantly influence the company, then I’m not going to be I’m not going to be able to tell them, hey, give me the 12,500 I can’t do that. I can’t say I want my shares right now. Why? Because if you were to pay one stockholder, you’d have to pay all all of the stockholders so because that’s, that’s the price you pay for all units being equal. So the price you pay for all units being equal, or one of them, is the fact that when you make a distribution, the distribution has to be equal to all the shares that are going to be outstanding. So in other words, if the company made 160,000, you’d think well, they could distribute, they have a choice they can make in that case, they could say, Do I want to take that money and distribute it to to the owners in the form of dividends, which the owners would like, but or you can take that money, and you can put it back into the company. And if you were to do so in such a way that you can generate more revenue in the future, that would increase the value of the company, which the owners would like. So it really depends on you know, what, what the what the owners want, or what the goal of the company is, in order to create wealth. Remember, the goal is to create wealth for the owners, not just give them cash, right? Some owners might have cash as their as their objective. And they might invest in a different way as owners that want to generate wealth over a longer period of time. So So if the company gave out the the money to the owners, then the owners would have that money, but they wouldn’t, the company wouldn’t be using it in order to generate more revenue. Now, for large established companies, that’ll typically be the case, right? I mean, because the company might not need that those earnings in order to generate more revenue, if you’re talking about the phone company or something like that, they’ve already got all the installation all in place, maybe they don’t need a lot more capital investment at this point. And they and they’re running smooth, right, they got up, they’ve got what they need, people might then put money into that type of company expecting a return expecting dividends, which many people might do towards the end of their life or something like that, where they’re retired, and they’re living on the dividends, they want the cash, as opposed to a company that’s up starting that, like, if you’re trying to build the infrastructure of your company, then you’re going to want to say, hey, look, I need to hold on to that money, because I’m going to put it back into the company. And that’s going to increase value. And that means the value of the stock will increase over time. And that’s going to be creating more wealth, but it’ll take a longer period of time to do that. So notice, that’s kind of the trade off that you’re going to have, and you can kind of break down the earnings. So you can break down the earnings to the earnings per share. But that doesn’t translate into the actual dollars that you would get in the form of basically distributions by the company, which would be dividends, which is something that the company would have to decide how do they decide,

29:06

the Board of Directors and the management would help to to make that decision Board of Directors is being voted on by the stockholders who create the board of directors who hire the management that would then be making these decisions as to how much of the earnings should they be distributed in the form of dividends. So if we compare this to all the other statements here, then remember we got the balance sheet where we stand at a point in time assets equal liabilities plus equity, you can think of this as assets minus liabilities equals equity. So this section down here represents the book value of the company. The top part of this section, preferred stock common stock paid in capital, as we saw on a prior presentation represents the what the owner put in when the company issued the stock for the initial investment of the owner. The retained earnings represents the accumulation of revenue over time. That has not yet been distributed in the form of dividends, they’re they’re retaining it, the company is holding on to it so that they can use the assets that have been generated there for future for future growth. So and then the income statement is related to the balance sheet, because it’s going to be feeding into this valuation the equity section feeding into the retained earnings. The income statement, in essence, if you break it down to its components is simply revenue what the company has earned minus expenses, given us the net income, or in this case, earnings after taxes, the link between the balance sheet and the income statement is what we call the statement of retained earnings. It’s linking the balance sheet in the prior period last year, or the prior year before last year to last year’s balance sheet, the one we’re currently putting together. So that means it’s going to be saying give me the retained earnings, which is going to be the retained earnings, we’re looking at the retained earnings, the accumulation portion of the stockholders equity as opposed to the investment portion, give me the prior period, December 31 of the phone of the prior year before these set of income statements. And that’ll be the beginning period for this component, then we’re going to add to it the earnings available to the common stockholders. That would only be the case if there were preferred stockholders, because we had to basically account for the preferred stockholders, which we did up here. And then we’re going to then we’re going to subtract out the dividends, which is the amount of the dividends that went out not to the preferred stockholder. But to the common stockholders. This again being kind of a major key, that’s not included on the income statement. Most of it most of the differences, of course, net income, the dividends are the things that are that we need the statement for, to basically tell us the other piece of the story to get the reconciliation between the prior period, and the current period, that’s going to be reported on the balance sheet in the account of retained earnings. Once again, these two accounts you want to think about them at are these these statements the balance sheet and income statement and the linking statement of retained earnings, you want to think of one set of statements that are put together with one accounting method that being an accrual basis, recognizing revenue when it is earned expenses when incurred in order to help generate revenue in the same time period. And then you’ve got the statement of cash flows, which you can think of as basically reformatting, you could think about doing the statement of cash flows after having done the balance sheet and income statement if you were to construct these items. And the statement of cash flows is basically taking that information, reworking it not on an accrual basis, but rather on a cash flow basis, the cash flows that are going in and out of the company, the net income will typically tie into the statement of cash flows and the cash flows from operating activities. This is a cash flows from operating activities and an indirect method which is the most common method that will be used. And therefore the net income will then tie into this item here and then you’ll have reconciling items, which will take net income that was on a on an accrual basis and give a reconciliation to get to basically net income on a cash basis otherwise known as net cash flows from operating activities. And then you’ll have cash flows from financing investing activities and the cash flows from the financing activities. Bottom line of the cash flow statement will then tie out to the balance sheet number balance sheet represents cash as of the end of the time period. So if we’re talking about financial statements, for the for the year ended December 31, meaning January through December balance sheet will be as of December 31. As of that point in time, the bottom line of the statement of cash flows will end at that cash balance at the end of the time period after having considered the activity or the change of cash what has happened in terms of activity or flow during the period during the year.