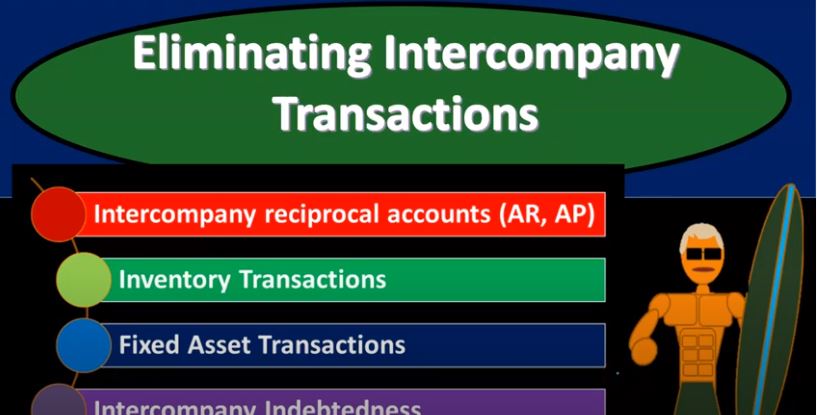

Advanced financial accounting. In this presentation we will discuss eliminating intercompany transactions, the objective will be to have an overview of the intercompany transactions, the types of intercompany transactions and the basic elimination entry for those intercompany transactions get ready to account with advanced financial accounting intercompany transactions, we’re going to start off by listing the intercompany transactions as we list them. Remember, our objective is in essence to remove the intercompany transactions.

Therefore, we want to think about what are the intercompany transactions? What category do they fit into? And then what are going to be the effect on the financial statements? And then of course, how can we reverse them? So if we have the intercompany reciprocal accounts is a type of transactions for example, we could have a cash accounts receivable and accounts payable involved, meaning one company if we think about a parent subsidiary relationship that we’re going to be consolidating, we might have a receivable Books for the parent and a payable on the books for the subsidiary that we would then have to reverse. Now you might say as you think about these, there could be other like notes payable and receivable and so on, that are reciprocal. These are pretty basic pretty easy, for the most part because they should be equal and opposite on the two sets of books and therefore an easier thing to remove. As you think about the receivable and payable. However, you might say, what about the other things that could be included in that type of transaction, such as possibly inventory or something like that a sale that’s going to be taking place. So when we think about the reversing entries, we may want to think about them a little bit separate by basically separating those out. In other words, we’re not typically we may not just say, Hey, this is going to be the the actual journal entry that took place and reverse it and in that format, we might reverse In other words, these accounts and then deal with the other side of the accounts that could be affected the inventory, the sales, the cost of goods sold. So these then are usually going to One of the easier type of things that that we can, we can reverse hopefully. And for example, the accounts receivable subledger, we would show we would show that it was an intercompany sale by who, who was owing us money and the sub ledger for AP, which show who money is owed to and we can reverse that out, then we have the inventory transactions. Now these are going to be a little bit more difficult.

02:24

And again, you might say, hey, there’s some overlap here. If there’s an inventory transaction, isn’t it quite possible that in that inventory, transaction sales was affected, for example, in the inventory, transaction, and accounts receivable and whatnot? Well, that could be the case. But again, we could kind of separate those those items out. So when the inventory transactions, we could we could try to group together, you know, the effect of the inventory going from, let’s say, a parent to the subsidiary or subsidiary to the parent. And then of course, we got to think about how we’re going to reverse those, that’s gonna be more complicated, because when you think about inventory transactions, then you got to think about Whether or not the inventory is still on the books of the parent or subsidiary, and whether or not it was sold when you have that, and then the case of the markups that could happen with them, it can be a little bit more confusing to do that reversal process. So we’ll think about that later. Then we got the fixed asset transactions. So we could have transactions intercompany transactions related to fixed assets. And again, they’re a little bit more complex than other types of transactions, possibly even just an intercompany reciprocal accounts. Because of the other things that could be involved there. We could have depreciation gains and losses, if what not involved with those type of intercompany transactions and then intercompany indebtedness, which could be a little bit more difficult than simply this reciprocal account, because of course, we have other things that could be involved such as the calculation of interest, we’re going to be focusing in on first now we’ve taken a look at these to some degree in the past. Our focus now is going to be on the inventory training. Transactions at this time. Okay, arm’s length transactions related party transaction. These are we’re going to compare and contrast these these two things. And when you think about an arm’s length transaction, from an accounting standpoint, you’re typically thinking about a transaction where you’re saying, hey, this transaction happened within the market, there’s a market transaction. These are unrelated people. And therefore, when you think about the price of the exchange that took place, you would assume there was an equal and opposite exchange of goods and services, assuming that both parties have the information necessary in order to make a good transaction. So if it’s a related party transaction, then all that kind of goes out the window, we have a problem then, from an accounting standpoint, because now you have a related party transaction, we can’t depend on the transaction itself. We can’t depend on two independent people being self interested, resulting in a transaction that would be at market or fair value.

04:55

And that’s going to be a problem. Obviously, that’s going to be one of the issues that will be involved. If you’re talking about Parents subsidiary relationships and transactions between like parents and subsidiaries. It’s just the same thing. As of course, if you had a transaction between siblings or spouses or whatnot or son, you know, cousins and stuff like that the transaction kind of loses its validity in some degree. If a parent give something to them, they might sell something to their child. But of course, it might not be for them the same market price we’re not. If something was sold from a parent to a sibling, we’re much more likely to question the market value of that transaction, part of it might have been a gift, right? Which there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just, we can’t rely on the market to basically tell us the value of the item. Whereas if the parents sold it to a third party, so the same property to a third party, then of course, we would say, well, the two people are self interested, they must have negotiated, you know what you would think it would be a market price. So arm’s length transaction is what we typically want to see in accounting. And when we don’t see it, then we’re we’re going Gonna have to, you know, think about what we’re going to do about that. So transactions with parties outside the the economic entity. So again, of course that means it’s going to be somewhat unrelated to the entity. So not a subsidiary not a, you know controlled entity, typically, are the type of transactions included in the income statement. So that’s basically what we want. Of course, on the income statement, we want transactions included on the income statement, if you’re thinking about a parent subsidiary type of relationship. And and if you’re thinking about a consolidation statement to we’re thinking about transactions that we want, that were made to outs people outside on an arm’s length transaction, that’s basically what we want to include the related party transactions we typically want to eliminate. The consolidated financial statements should report the interactions with parties outside the organization related party transactions, which you could also call non arm’s length transactions. So non arm’s length transit Actions intercompany transactions generally need to be eliminated during consolidation. So when we think about our consolidation process, the related party transaction, non arm’s length transactions are going to be those intercompany transactions. And of course, those are the things that we need to eliminate.

07:17

We can’t have those being reflected in the consolidated financial statements, possible intercompany transactions that would need elimination, there could be sales and purchases, that were intercompany parent to subsidiary subsidiary, as a parent, there could be interest, there could be debt, you know, from one to the other, resulting in interest. There could be dividends, there could be security holdings. So these are types of things that could, you know, come about as intercompany transactions that will then we’re then going to have to consider how what’s the effect on the financial statements and how can we basically eliminate them intercompany transactions are eliminated, whether the subsidiary is wholly owned or partially owned. So you might have a question in your mind you might be saying, Okay, well, what P owns s. But you know, to have a controlling interest, they only need over 51%. But they don’t need 100%. So what if there’s going to be these intercompany transactions with like a controlling interest, that’s not a wholly owned subsidiary, well, we’re still, we’re still going to basically remove, we’re still going to remove the intercompany transactions. So when we do the consolidation, we’re going to say consolidate it and say, save the parent and the subsidiary will have have the total transactions, then we’re going to remove, you know, entirely the intercompany transactions that could be between those two entities, we’re not going to remove In other words, like if there’s a 70% interest in the parent to the subsidy or when it’s not like we’re just going to remove the 70% controlling interest. We’re going to remove the intercompany transaction the entire amount.

08:53

And you might justify that by saying well look, again, the consolidated financial statements are there to To represent the assets and liabilities that the owner has based or the parent company, generally we’re thinking about the parent company, when we’re looking at the Consolidated Financial Statements has control over, right, and the income statement represents, you know, the performance of those net assets that basically the parent company has control over. And so from that perspective, it would make sense to basically remove the entire amount of the intercompany transaction because the parent would have control, in essence, ultimate control at the end of the day to allocate assets and resources. So you know, you wouldn’t want to allocate assets and resources to yourself if you have control over to do so it would make sense to eliminate the intercompany transactions intercompany loans so if there’s intercompany loans, fairly straightforward to take, take off the loan amount, right because then you would have the loan payable on one side of the books, whether it be parent or subsidiary and the receivable on the other side. So the loan payable That’s a liability account, we would remove it by doing the opposite thing to a debit in it. And the receivable is going to be an asset account on either the parent or the subsidiary, you would have a debit balance, we would take it off the books with a credit, then we have the sale from P to S R to outsider. So this is one we’re going to we’re going to spend a little bit more time on, what if something happened where the parent sold to the subsidiary, then the question is, well did the subsidiary resell it or have they not yet resold it, because if they’re still holding on to it, there’s going to be a different treatment. So if there was a sale from SA p to s, and then S sold to an outsider, then you’re still gonna have to remove the the revenue on the sale from P to s, right. So you’re gonna have to because the sale from P to s wasn’t really a sale to an arm’s length sale, and then you’re gonna have to remove the cost of goods sold. In essence the cost of goods sold that was from S to the outsider. Because the cost tickets sold would be overstated there. So this one gets a little bit more complicated because you could think about this as reversing the full intercompany transaction.

11:09

Or you could do what we’re going to end up doing, which is kind of netting it out and think about how you can reverse the thing as efficiently basically as possible. So we’ll spend a little bit more time on these shortly, then we have the sale from P to s, and then S has not sold it yet. So what have you sold from the parent to the subsidiary, and then the subsidiaries just holding on to it? Well, in that case, then no sale really took place, right, because s still didn’t sell sell the inventory. So when just from P to s, the sale is basically, you know, kind of like not a legitimate sale from an arm’s length transaction perspective. So we would reverse the revenue so we’re going to debit the revenue to take the revenue off the books, reverse the cost of goods sold credit cost of goods sold, because it’s a debit accounts that will credit it to take it off the books, and then we’ll credit the inventory. We’re going to credit the interest For two way for the gross profit, realized, so that’s going to be the gross profit going off the books. Now you might think, you know, why don’t why aren’t I just reversing the entire transaction which you know, the normal transaction would be, you know, a debit to say cash a credit to revenue, a debit to cost of goods sold a credit to inventory, because the other side of the books, you know, that would be what p would be recording. And then S would be recording what they would be recording inventory going up on their side for the revenue portion, and they would be recording cash going down. So the cache would net each other out and then the revenue would count. So you can see this is kind of like the net, they would have to do this is the most efficient way for us to reverse this rather than reversing the entire journal entry on P and S books. So let’s we’ll spend a little bit more time to kind of move that concept over so we get once again going to spend some time here where we have this concept the sale pts then to an outsider, where we’re reducing the revenue with a debit and reducing the cost of goods sold and then the sale from P to s as has not yet sold it. And then of course we can we can apply some of the same principles to what if it was the other way. This is going to be what we’re calling a downstream sale went from parent to subsidiary, and then what happens if it’s an upstream sale subsidiary to parent so similar concepts can can apply. So we’ll start to move that over in future presentations.