In this presentation, we will take a look at notes receivable. We’re first going to consider the components of the notes receivable. And then we’ll take a look at the calculation of maturity and some interest calculations. When we look at the notes receivable, it’s important to remember that there are two components two people, two parties, at least to the note, that seems obvious. And in practice, it’s pretty clear who the two people are and what the note is and what the two people involved in the note our doing. However, when we’re writing the notes, or just looking at the notes as a third party that’s considering the note that has been documented. Or if we’re taking a look at a book problem, it’s a little bit more confusing to know which of the two parties are we talking about who’s making the note who is going to be paid at the end of the note time period? We’re considering a note receivable here, meaning we’re considering ourselves to be the business who is going to be receiving money. into the time period, meaning the customer is making a promise, the customer is in essence, we’re thinking of making a note in order to generate that promise, that will then be a promise to pay us in the future.

01:13

So in essence, you can think of a note as a type of promise, we are the business. In this case, we’re providing a service, and therefore the customer is making a promise, in order to pay us at one at some point in the future. We’re asking for a bit more commitment of the promise, then we would typically have under an accounts receivable situation, and typically the reasons for that would be that the amount of the sale was greater possibly. So it’s a bigger dollar amount that we want a formal documented promise to pay us and or we’re going to charge interest on on the loan that we’re making here. Now remember that although we’re thinking of it as a promise from the customer, it’s probably the case that we asked the business who deal with these type of documentations and promises All the time, are probably the one that are going to generate and print out the formal type of documentation as part of our business that the customer can then sign as the promise to pay in the future.

02:12

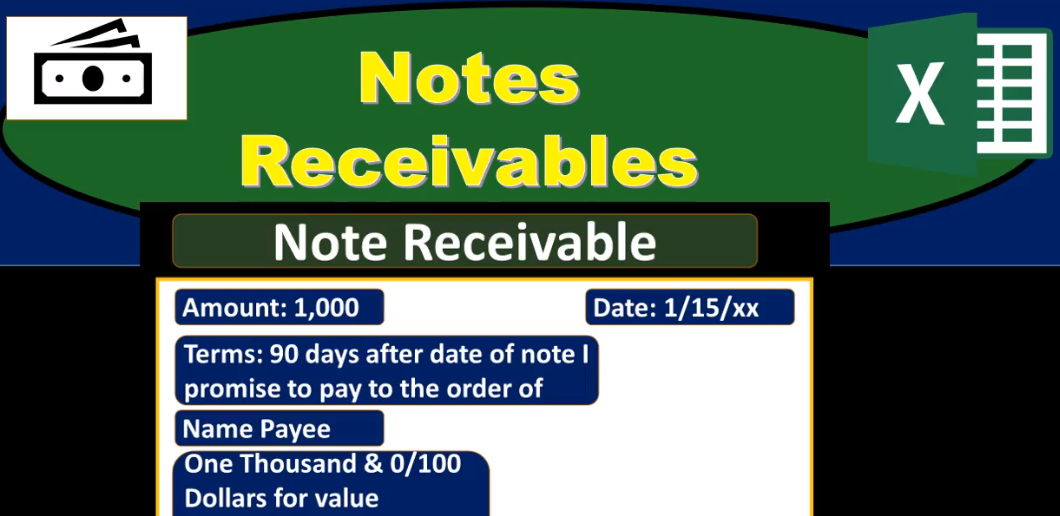

But from a conceptual standpoint, we can think of it as the customer, basically documenting or making this filling out this promise in order to pay us in the future. A couple critical components that will typically be in any note receivable, even a fairly simple note receivable, which we will typically have documentation for, and have a formal written document when it’s a larger dollar amount. And we’re charging interest there’s a larger or longer timeframe involved than the normal 30 days or 60 days possibly have an accounts receivable. So we’re typically going to have the amount we’re going to have the amount of the note that would be if we sold something as the business then we maybe had a sticker price of whatever we sold of $1,000 and therefore our are owed. I think thousand dollars, there’s gonna be a promise by the customer to pay us for what they purchased, then we’re gonna have the date of the note, typically the date that the transaction happened, the purchase happened, then we’re going to have the due date.

03:12

And oftentimes the due date is going to be written something like this 90 days after date of note, I promise to pay to the order of event we’ll have the name of the payee. And that’s for a couple different reasons. Note that this isn’t just doesn’t just have a date at some point in the future. Typically, a lot of times the note will be written in wording such as this. And part of that could be that it makes it easier for us if we’re the business who are generating this note for the customer to sell and we do this often, then it could be a pretty standard way for us to just say 90 days from any point of the date of the note and that makes it easy for us to make like a template to make the notes but for any in any case the the terminology will often be like 90 days, 30 days, 120 days for the note We’re going to be dealing with notes here typically shorter terms, meaning less than a year, when we’re considering the notes that we’ll be working with. Now, it’s important to keep straight at the payee, as you can see from the wording of the note is who we are promising to pay.

04:14

So that’s in essence, us, that’s the business, that’s who we’re going to get paid at the end of the time period, the principal amount plus the interest. So the other component then will be the interest, we’re going to pay 1000 and dollars for value received with interest at the annual rate of 10%. So that’s how much is going to be paid. Note how much is going to be paid. Then in terms of two components. One, the principal component, this is kind of like the loan that we gave, we didn’t give them a loan in dollars. We didn’t loan out the dollar amount, but we sold something with a sticker price of 1000 didn’t get paid yet at the point of sale and therefore are in essence, loaning this money renting the money out

04:56

to the customer, and we’re going to get paid that money at the end. If the loan term 90 days typically greater than a normal accounts receivable term, and we’re going to get paid interest on top of the loan. Note what’s not being said here, if we don’t have an official end date, we have 90 days from the due date. So we’ll have to figure out when that will be when is this actually due. And we don’t have the actual amount that we’re going to get, we know we’re going to get $1,000. That’s the sticker price. And then we got to figure out the 10%. This is typical in many notes. So if you read a note, oftentimes, it’s not going to give you like an amortization schedule or an interest type of calculation. Not required to have that in the note because you can figure it out. And so oftentimes, it’s not included, but you probably going to want to figure that out. And we’ll take a look at that. And we’ll need to know that in order to make the payment at the end of the time period. And then we’ve got the maker of the note and remember that is going to be in our case, the customer we’re imagining the customer is the one that’s making this promise. So that’s it The thing that’s often confusing when we think about these notes who’s who it seems obvious, but it can be a little bit confusing in terms of who’s the payee, and who’s the maker. Although we, as a customer, when we go and finance something, don’t think of ourselves as writing out this little promise, but you can think of it as making this promise as if we’re writing this out. We’re saying, Hey, give me a piece of paper.

06:21

I don’t have the time right now, I don’t have the money right now. But my you know, my word is good. Give me a piece of paper. And I’ll write out to you a little promise a little formal promise here, right? Here’s the date. Here’s the amount I promise to pay it within 90 days. And I promise to pay you not only the principal but 10% interest for giving me the service of loaning me this money for a certain time period, and then the person making the promise the customer in this case, the maker signs the note. Of course in practice, the person who has this document made formally made would probably be the business then being the person who is used to making this documentation Then allowing the customer to read it and go through it and sign it as well. So if we look at the components, remember that the principle is up here, we were going to break out these two components of the payment of the note at the end of the time period in two components, one the principal, the amount of the original loan to the interest, then we’re going to have the due date, which is here 90 days from the date of the note, which we’ll have to figure out what When will that actually be, then we’ve got the payee who’s going to be paid at the end of the time period, it’s going to be paid at 1000 plus the interest who’s going to get that payment at the end, we have the interest rate, in this case being 10%. And the maker of the note, the person who signed the note the person who made the promise for the note. Okay, so then we’re going to figure out the maturity date.

07:50

This can be a little bit more confusing than you would think. Because if we’re saying it’s a 90 day note, and that we’re saying the due date was 115 Well, we really got to think well now, I mean, each month has a different number of days in it. So it’s actually a bit a little bit confusing to go through and figure out when the actual date of maturity is. And this is actually a common problem. Of course, a computer can help us out when we generate this. And they’ll typically give us the duty because it could be computer generated. But note that when you’re working problems, and when you’re figuring this stuff out, and when you’re trying to just say, What’s 90 days, from this due date, it’s a little bit more confusing than you might think. And you want to have a system if you’re doing a test question to be able to figure that out. And if you’re in a system where you’re figuring this out all the time, you know, have some computerized system or just note that it might be a little bit more confusing than you would think at first. So we can think about that by saying that, okay, we’re gonna count up 90 days, there’s about 30 days in each month, but it’s starting on January 15.

08:51

So we can start off with a kind of a little subtraction problem, we can say, well, there’s 31 days in January, and we know that the note date is as of today 15th. So 31 minus 15 means there’s 16 days left. Now be careful because it depends on whether or not we’re going to be counting the day of the note term like this 15th day. So the question is, does that count in the term of the note and you can have to be kind of careful on that. So if you’re off by basically a day of a problem of a computer problem or something like that, or a multiple choice problem, it may consider the fact that well, is this 15 day included or not? If it is, then we’d have to add to that one more for this day for the 15th. We’re taking the difference between the 231 minus 215, which would start at the 16th. You can count on your fingers, right? 16 1718 up to 3116 days, then we can count up from there. We’re know we’re doing around three months, because it’s 90 days. So we’re going to say the days in February, we’re going to say it’s 28 and this year, and then we’re going to say the days in March are 31 And then we’re going to consider what we need to be at 90 days. So we can just figure out where are we going to live in at the end of this, we’re going to say, well, 16 days and Jen that are left in January plus 28 days plus 31 days, that gives us 75, we need to get up to 90, that’s not going to complete a whole nother month.

10:21

So how many days then are we going to need in April, it’s going to be 75 minus 90, or 15 more days. So this last piece, we’re going to say days in April or the due date, is going to be April 15. So in other words, if we calculate this one more time, we’re going to say we have 16 days in January plus 28 days in February plus 31 days in March plus the 15 days, 15 days in April, and that gives us our 90 days. So that means the due date is going to be here on April 15. So just be aware that you did catch activation can be a little bit tricky. Okay, so when we record the note, it’s a pretty easy thing to do to record the note, but often very confusing for people. When you see this note, you see this note and you say, oh man, there’s, there’s a principal amount, there’s an interest rate of 15%, or there’s the 90 days of the due date. And so you would think that when I record the note, it’s going to be fairly confusing. But really, when we record the note, all we need is this 1000. And so it’s deceptively easy to record the note, the interest of the note and the due date doesn’t come into play until time passes, we haven’t earned any interest. As of the day of note if we sold something for $1,000. And they gave us a note saying they will pay us in the future.

11:46

Then all we have to do is record the note at this time period, interest accumulates as we basically rent them money. It’s rent on the money so we have no rent on the money when we just gave the note sort of Record the note, if we sold something for $1,000, we would just record the sale of $1,000. And then we debit instead of accounts receivable, notes receivable. So note, it doesn’t matter all this other stuff like I don’t need any of this stuff, all I need to know is that there’s a note for $1,000, I don’t need to know the interest rate, I don’t need to know the terms. I don’t need no any of that in order to record the notes. So just be aware of that can be can be really confusing, because of too much information to put the note on the books. Now of course, if we made a sale and we sold inventory, we would have the other side of that cost of goods sold and the inventory going down. Both so this is the same transaction just look this should look familiar for us making a sale on account. Instead of having accounts receivable we’re now having notes receivable.

12:49

Typically because the amount of the note is a larger dollar amount. We want to charge interest on the note typically the term of the note being longer term and therefore have any formal written document. Then we then will be tracking it not in the subsidiary ledger for accounts receivable, but in a separate notes receivable and tracking both the principal and the interest. So same transaction, just replacing accounts receivable with notes receivable and pretty straightforward transaction, then when we’re going to calculate the interest, we’re going to have to figure this out so that we know how much it’s going to be paid to us or do to us at the end of the time period. So note at the beginning of the time period, there’s only $1,000 do us and that’s it. There is no interest yet there’s no interest until time passes after time passes, then they’re gonna owe us the interest because we rented them money and they have to pay us rent on the money interest on the money. So how much are they gonna have to pay us because of the rent on the money? We’ll figure that out. Now we got $1,000. The interest rate is 10%. So 1000 times 10%. And rubber fits in a calculator.

13:57

We’re gonna say 1000 times point one Or 10%. point one if you move the decimal over two places is 10%. That’s $100. So that gives us the hundred dollars. And then I typically think about it this way, remember that this interest and we’ll go over this in more depth. Later we’ll figure out different ways to calculate the interest. But interest is for a year. So it says it here an annual rate, even if it doesn’t say annually. Whenever we think about interest, we think about it in terms of a year. So just we have to understand that whenever we talk about interest, we talked about in terms of a year, even though the note term is rarely for one year, it’s often for a series of months. And we’ll have to then break out this interest amount which would be for a year if the note was out for a year into some monthly amount. So in order to do that, one way to do that is we can take the days in a year or 360. And we could take that hundred dollars divided by 360 days, or it doesn’t come out even and we’ll have to deal with this point too. 777, right? And so that’s going to be the amount. Now where did we get the 360, there’s 365 days in a year, typically, we’re going to use a rounding a number to make this an easy calculation for simple interest, meaning we’re just going to take 12 months times an average of 30 days and each month, or 360 days.

15:21

And that’ll give us a nice, even way to calculate this simple interest that we’ll be calculating. So once again, we have $100 divided by 360 days in a year, that’s about 28 cents per day. If we round it, so 28 cents, we need to be careful about this rounding, we cannot get away from rounding, it’s always going to be a situation so we could make problems that come out perfect all the time, and they don’t round and they round out perfectly. But in real life, there’s going to be this issue. So if you’re off by a couple, a little bit, a couple dollars, it could be a rounding issue, and we always have to be aware of that. So anyway, We have the 28 cents per day, and the number of days of the note is 90 days, then we can multiply that out. And we get the 25. Here. Again, if you if you do the math here, and you say point two, eight times 90, it’s actually 25.2. And so that’s a rounding issue there. And remember, this wasn’t actually 28. It’s 100 divided by 360 is actually 27 2.7 7.277 times 90, is 25.

16:34

So just if we use Excel, and we’ll take a look at Excel, we’ll be able to know how to deal with these rounding issues and make it exact. So just note that those are always going to be something that we have to deal with things aren’t going to be perfect in terms of dollars and pennies. We need to figure out how we’re going to deal with these rounding issues. And when we’re off by $1 or so. We need to recognize that say it’s okay, well, it’s rounding we’ll figure it out. Okay, so then if we’re going to say that the interest is $25 that will be earned at the end, then when we get paid at the end of the time period, we’re going to get paid, then what’s our journal entry going to be? Well, cash is going to be received and the note receivable is going to come off the books. Now we’ll see this with an example problem with a trial balance, it’s a lot easier to see if you have a trial balance. But the note receivable we put on the books remember by debit of 1000, it’s kind of like accounts receivable has a debit balance, we need it now take it off the books because we’re going to get paid, we’re going to get paid more than 1000 1000 plus the 25.

17:40

But we’re going to take it off the books for the amount that’s on the books 1000 that that 25 is going to be interest revenue. So it’s going to be revenue that we earned we earn revenue based on not the sale when we earned the thousand dollars when we sold it. This is revenue that we earned for renting money in essence, and it’s going to increase revenue. Increasing an income statement account and revenue income statement account, which will increase net income. And then the cash we get will be the 1000 to 25. So remember, we made the note for 1000. When we put it on the books, we only put it on for 1000. Then we had to take it off the books taking that thousand dollars off. But at this point in time, we had earned $25 throughout the term of the note, and therefore we’re recording more revenue than we had recorded at the beginning of the note, because we’ve recorded revenue for whatever we sold at the beginning. Now we’re recording revenue due to the fact that we loaned out money, we made interest on the money, we rent in money. That’s how we earned this 25 increase in net income by the 25. And then we got then 1000 principal back, plus 25 interest, that’s how much it’s going to be paid to us at the end of note. Now, if the note is dishonored, we have the same kind of problem that what happens if they don’t pay the note. Then we’re still had earned the 25 We’re going to have to revert it to some other components.

19:03

But the due date of the note, we still need to do something meaning we need to take the note off the books it’s passed to do. And then we’re going to record the interest, we still earn the interest for renting the money. And we’re going to have to debit something we can’t debit cash. So we could put it back into accounts receivable, tracking it back into accounts receivable so that we can track in our subsidiary ledger, this customer, this individual that owes us money, and track that they still owe us that money somewhere. So we’re going to still record the fact that we earned interest revenue, we still need to take the note off the books because the term of the note had ended. And then we can put it back into accounts receivable as a holding account to let us know that we still have this dishonored note and we still want to try to collect on it and go through the collection process for there’s also a case that we might have an adjusting entry at the end of the note time period and we are happen because remember, remember that we make financial statements as of the end of the month or the end of the year. And the note term in this case is 90 days. So what that means is that, for example, here we have the notes term, it happened on January 15.

20:15

And we’re going to make financial statements as of January 31, then we’re going to have some days that fill in this month, where we earned revenue, we rented money out kind of like if we rented a house out, we earned revenue, but we’re not going to collect the rent. Until next month after the end of the close here. That means that there’s rental money that was earned, which we should recognize as earned it, we earned it because we loaned out what we loaned out, not a house in this case, but money. And so we should recognize it in this time period, even though we have not received the cash. That’s going to be an adjusting entry. So to do that, we’re going to have to figure out well, how much did we earn as of the end of the month. So it’s a 90 day note, but how much did we earn in January? We have to figure out Well, that depends on how many days it was outstanding, and the interest rate. So we’ll do a similar similar type of an interest calculation, we got the principal, we’ve got the interest rate is 10% 10% times 1000 is $100, then we’ve got the days in a year, this would be $100 per year, remember 360 days, which we’re saying 12 months, times 30 days to make it even 360 $100 per year times 360 days is point two 828 cents per day.

21:39

Again, that’s rounded, it’s really point 277. This is the same calculation we had prior. Now we’re just going to make a slight difference. We’re not going to multiply times that term of the of the note the 90 days but by only the amount of days that are remaining in the note which is 16. So if we did this in advance In a calculator, remember, what we’re saying is there’s 31 days in January minus 15. That means there’s 16 days left and you have to be careful in terms of are we going to count the day of the note or not. So if you, if you’re off by a little bit, that might be the difference if we’re counting the 15th, the day the note was created, or not, the difference when we calculated here, 31 minus 15, is not calculating, meaning if we counted it up on our fingers, we would count starting with 1616 1718, up to 31 would be 16 days. So if we do this calculation, and we’re going to say we had $100 of interest divided by 360, that gives us point 2777. And that’s about point two, eight times 16 days, and that gives us 4.44. Again, it’s not perfect, but it’s about $4 and 44 cents,

23:00

Now this amount seems minor and it is. So this adjusting entry. But if we had a lot of these adjusting entries or if the dollar amount was larger, this could be a material adjusting entry that we would want to make sure that we record in order to represent the financial statements correctly. as of the date we make them, the end of the month, the end of the year, sort of record the adjusting entry, we’d have to say that we have interest receivable of this $4 and 44 cents. In other words, at this point in time, we have the notes receivable already on the books when we first recorded this at $1,000. And we’re not going to record this amount in the receivable itself.

23:39

We’re not going to say the receivable is $4,004 and 44 cents, what we’re going to do is make another account called interest receivable and that’s where we’re going to accumulate the interest which is related to this note an asset asset have debit balances the receivable it’s going to go up by doing the same thing to it. Another debit Then we’re going to record the interest revenue that we earned. We didn’t get paid yet. We haven’t gotten cash yet. But we did record interest and remember, that’s just the rent on the money that we loaned out. Interest is a revenue account or interest revenue. The revenue account has a credit balance as all revenue accounts do. We’re going to make it go up by doing the same thing to another credit, increasing both the revenue account and therefore net income.